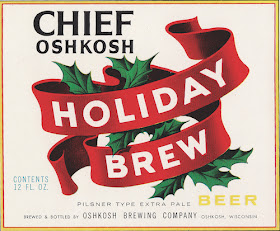

Here's a photo from the Oshkosh Daily Northwestern published the day after Thanksgiving 1961. We see David Uihlein, who had recently purchased the Oshkosh Brewing Company, posing with the re-designed tap handle for Chief Oshkosh Holiday Brew.

Each year about this time, OBC released its annual holiday beer. It never lasted long. Oshkoshers would usually soak it all up January. By the way, I recently collaborated with Bare Bones Brewery in Oshkosh on a recreation of Chief Oshkosh Holiday Brew from the 1950s recipe for the beer. It's slated for release December 17. More to come!

Friday, November 29, 2019

Tuesday, November 26, 2019

Barrel-Aged Black Friday in Oshkosh

A quick note about the Black Friday beer releases coming from Fifth Ward and Fox River this week.

At Fifth Ward they'll be tapping Oreo Job, a barrel-aged imperial stout conditioned on Oreo Cookies. That one clocks in at a hefty 11.5% ABV. Oreo Job is the latest issue from the barrel-aging program Fifth Ward began releasing beers from earlier this month.

And then there's going to be this at Fox River...

Black Fox began as a blend of Marble Eye Scottish Ale and Trolley Car Stout that was then aged for a year in rye whiskey barrels from Wollersheim Winery and Distillery of Prairie du Sac, Wisconsin. Look for the barrel-aged character of this one to pop. Black Fox will be available in 22-ounce, wax-dipped bombers and on draft when Fox River opens at 11 a.m. on Friday.

At Fifth Ward they'll be tapping Oreo Job, a barrel-aged imperial stout conditioned on Oreo Cookies. That one clocks in at a hefty 11.5% ABV. Oreo Job is the latest issue from the barrel-aging program Fifth Ward began releasing beers from earlier this month.

And then there's going to be this at Fox River...

Black Fox began as a blend of Marble Eye Scottish Ale and Trolley Car Stout that was then aged for a year in rye whiskey barrels from Wollersheim Winery and Distillery of Prairie du Sac, Wisconsin. Look for the barrel-aged character of this one to pop. Black Fox will be available in 22-ounce, wax-dipped bombers and on draft when Fox River opens at 11 a.m. on Friday.

Friday, November 22, 2019

Brewed Under the Old German Process

A 1913 advert for the Oshkosh Brewing Company, the “Best Equipped Plant in the Northwest.” This appeared in Volume 20 of Samuel Gompers' The American Federationist, published by the American Federation of Labor.

The bit about the "Glass Enameled" tanks is only partially true. OBC was also using pitch-lined wooden tanks at this point. And prior to the beer hitting those closed tanks it was fermented in open, wooden fermenters. The Old German Process!

The bit about the "Glass Enameled" tanks is only partially true. OBC was also using pitch-lined wooden tanks at this point. And prior to the beer hitting those closed tanks it was fermented in open, wooden fermenters. The Old German Process!

Tuesday, November 19, 2019

Oshkosh Lager Beer Cans, Then and Now

Here are a couple of cans of Oshkosh-brewed lagers separated by about 60 years.

The can on the left is from the late 1950s. The can on the right was filled at Bare Bones last Friday, November 15.

The 1950s Oshkosh Brewing Company can is made of heavy gauge steel with a flat top. You needed a church key to get any beer out of it. The label is printed on the metal. It weighs about three ounces. The Bare Bones can has a shrink-wrapped label and is made of aluminum. It weighs less than an ounce and has a stay-tab opening.

The version of the Chief Oshkosh can shown at the top was introduced in the spring of 1958. It was designed by Robert Sidney Dickens of Chicago. Dickens was a highly sought after package designer with clients such as Blatz, Hamms, Coca-Cola, and Quaker Oats. It was an expensive project for OBC. Dickens' charged $5,700; or about $50,000 in today's money.

The Bare Bones can was designed by Jody Cleveland, the head brewer at Bare Bones. Cleveland used the Dickens design as his model, updating it to give it a somewhat more contemporary feel.

The beer put inside those two cans is about as similar as the packaging would suggest. The recipe for Oshkosh Lager is based on the Chief Oshkosh Beer recipe from the 1950s. Cleveland made some slight adjustments to the recipe to make it more in line with current tastes.

Oshkosh Lager was introduced in February of this year. It was packaged in cans for the first time in May. That was a small run of hand-labeled cans filled on the brewery's countertop, crowler filler.

This time it was a much larger run of 27 cases packaged on a mobile canning unit. Canned six-packs from this run of Oshkosh Lager are now available at the Bare Bones Tap Room. Maybe next time, they'll box them like those 1950s sixers of Chief Oshkosh. But I wouldn't count on that.

The can on the left is from the late 1950s. The can on the right was filled at Bare Bones last Friday, November 15.

The 1950s Oshkosh Brewing Company can is made of heavy gauge steel with a flat top. You needed a church key to get any beer out of it. The label is printed on the metal. It weighs about three ounces. The Bare Bones can has a shrink-wrapped label and is made of aluminum. It weighs less than an ounce and has a stay-tab opening.

The version of the Chief Oshkosh can shown at the top was introduced in the spring of 1958. It was designed by Robert Sidney Dickens of Chicago. Dickens was a highly sought after package designer with clients such as Blatz, Hamms, Coca-Cola, and Quaker Oats. It was an expensive project for OBC. Dickens' charged $5,700; or about $50,000 in today's money.

|

| Robert Sidney Dickens |

The Bare Bones can was designed by Jody Cleveland, the head brewer at Bare Bones. Cleveland used the Dickens design as his model, updating it to give it a somewhat more contemporary feel.

The beer put inside those two cans is about as similar as the packaging would suggest. The recipe for Oshkosh Lager is based on the Chief Oshkosh Beer recipe from the 1950s. Cleveland made some slight adjustments to the recipe to make it more in line with current tastes.

Oshkosh Lager was introduced in February of this year. It was packaged in cans for the first time in May. That was a small run of hand-labeled cans filled on the brewery's countertop, crowler filler.

This time it was a much larger run of 27 cases packaged on a mobile canning unit. Canned six-packs from this run of Oshkosh Lager are now available at the Bare Bones Tap Room. Maybe next time, they'll box them like those 1950s sixers of Chief Oshkosh. But I wouldn't count on that.

Sunday, November 17, 2019

The Wildcat On High

There once was a brewery on High Avenue. It was a secret brewery. An illegal brewery. It was there during Prohibition when Oshkosh had a flock of bootleg brew houses like the one at the southeast corner of High and Division streets.

The brewery is just a small part of the story of this place. That corner was once full of life. Its peculiar history dates back to the early 1870s.

The Fowler House Hotel

In the summer of 1870, an English-born cobbler named Edwin Fowler bought the property at the corner of what was then High and Light streets. In 1876, Fowler put up a building there that would stand for the next 110 years. It was a two-story, wooden structure encased in brick with a roof made of tin and iron. The image below is from the late 1940s. The exterior of Fowler's old building hadn't changed all that much in the intervening years.

For more than 70 years, that was known as the Fowler House Hotel. Its first keeper was William Perrin, an English immigrant who came to Oshkosh in 1850. Perrin worked in a sawmill before he went into the hospitality business as a steward on a steamboat. In the early 1860s, he went ashore to become a hotelier. He ran at least three other hotels in Oshkosh prior to opening the Fowler House on June 15, 1876. Perrin was the guy who built the template the Fowler House would follow for decades to come.

This was not the Athearn. The Fowler House was among the cheapest hotels in Oshkosh. A room could be had for a dollar a night; about $25 in today's money. With rates that low, Perrin had to sell more than just lodging to make a buck. The hotel's profit center was the saloon that squatted in the street-corner portion of the first floor.

The Fowler House became popular with what the Daily Northwestern referred to as "the country people." That meant farmers coming to Oshkosh to sell their hay, produce, and livestock; or just to get the hell off the farm and live it up for a little while in the wicked city. The Fowler House and the Commercial Hotel, located directly across Light Street (now Division), were twin beacons for these folks.

The Lay of the Land

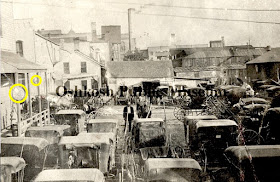

That busy photo above was taken from behind the Commercial Hotel looking east towards the back of the Fowler House. The yellow circles halo Oshkosh Brewing Company beer signs. They hang from both the Commercial Hotel, in the foreground, and the Fowler House in the background. Immediately to the right of the Fowler House is an attached house that served as the hotel's kitchen. At the extreme right is a portion of the Fowler House barn where guests stabled their horses.

The map below is from 1889. It details the layout of the neighborhood surrounding the Fowler House.

The 1889 map also shows the expansion that took place at the Fowler House. By this time there were two-buildings: the original hotel at 67-69 High and the addition to it at 61-65 High. They were connected by a passageway that provided access to the 25 rooms on the second floor of the 61-65 High address. Just to the east at 57 High is now The Reptile Palace bar.

A Canadian from Michigan

William Perrin quit the Fowler House in 1894. The hotel closed a couple of years later. In 1897, while the building sat vacant, two fires almost demolished the place. Both fires were thought to have been set by arsonists. The second fire, in the wee hours of October 27, 1897, left three firefighters injured and the building nearly gutted.

The Fowler House was quickly repaired and was back in business the following year. Over the next few years, a series of keepers shuffled through until William Crook arrived in 1906. Crook’s tenure coincided with the hotel's most colorful period.

William J. Crook was born in Canada in 1863. But most of his early life was spent in and around Manistee, Michigan. He’d started working in the sawmills there while still in his teens. Crook appears to have become familiar with Oshkosh in the 1890s. If he was coming here to look for a wife, he’d come to the right place. In 1896, the 33-year-old Crook married a 24-year-old Oshkosh woman named Louisa Hakbarth. Bill and Lizzie moved to Seattle after their marriage, but by 1905 they had returned to Oshkosh.

Crook took a job running a ramshackle saloon at the tip of the v-shaped intersection of Jackson and Light (now Division) streets. The place was surrounded by industry. It had formerly been the city market where local farmers sold their goods.

Crook stayed there for just a year. He took a lease on the Fowler House in November of 1906. His first 13 years at the hotel were relatively serene. Crook mimicked Perrin’s successful run, offering cheap accommodations and plenty to drink.

But the Fowler House formula came undone when the Wartime Prohibition Act took effect in the summer of 1919. That was followed by National Prohibition in 1920. Crook closed the bar at the Fowler House. He attempted to make up for the lost revenue by diversifying. He opened a tire sales and repair shop in the barn behind the hotel. The offices of Crook Tire Co. took over the space that had formerly been occupied by the hotel’s saloon.

The tire business wasn’t enough. Crook added another revenue stream; a Yellow Cab Company that he based out of the hotel. In Oshkosh, this sort of entrepreneurship was not how most bar owners responded to the dry law.

Crook’s Dilemma

When Prohibition arrived, the majority of the city’s saloon keepers immediately converted their bars into speakeasies. But for Crook, that option entailed more than just the risk of arrest. Crook didn't own the Fowler House, he was leasing it. If he were to get busted on a dry-law violation he stood the chance of losing not only his lease and livelihood, but the roof over his head. Bill and Lizzie Crook and their son Cyrus all lived at the hotel.

But operating within the law was hardly more appealing. The hotel was within walking distance of at least 10 former saloons that had become speakeasies. All that business was being drained away. It finally became more than Crook could take.

In 1925, he ended his lease on the Fowler House and purchased the property outright. Shortly after, Crook moved the tire company office out of the corner space and put the saloon back in. Of course, he couldn’t call it a saloon. His license said it was a soft-drinks parlor. It was anything but.

Crook wasn’t at all tentative in his new endeavor. When he began violating the dry law he seems to have done so with a flagrancy that was uncommon even in sodden Oshkosh.

The Fowler House speakeasy had soon caught the attention of local authorities. Crook’s bar was being investigated by Frank Keefe of the Winnebago County District Attorney's Office. Normally, the county DA didn’t like to get involved in the affairs of Oshkosh’s thriving bootleg beer and liquor scene. Here was an exception. Crook was not only selling liquor over his bar he was also retailing bottled booze for carryout. Keefe later alleged that those violations were compounded by the bar's popularity with an underage clientele.

On May 14, 1928, the Fowler House was raided. Crook managed to avoid arrest. Emil Harder, a Swiss immigrant who co-managed the bar with Armin Meister, was taken into custody. Harder was slapped with a $250 fine; about $4,000 in today's money. He also lost his job after he promised the judge he'd go straight and never do anything like it again. Crook had no intention of quitting. He hired Herman Priebe to be his new bar manager and re-opened the saloon. Then he upped the ante.

A wildcat brewery was installed in the basement of the Fowler House. Crook had no experience making beer. None was needed. The brewery was almost certainly a partnership with one of the local beer bootleggers operating in Oshkosh during this time. It would have been a standard arrangement: Crook supplies the space, the bootlegger supplies everything else. And the money comes rolling in.

It was a bold, perhaps foolhardy, move for the owner of an establishment already under the scrutiny of law enforcement. Crook had to have known he was pushing his luck. He couldn't have been too surprised by the result.

The Fowler House was raided again on the Saturday afternoon of February 22, 1930. This time it was federal agents who busted in. And this time, Crook was arrested. The feds found beer and whiskey at the bar. They found the brewery in the basement and promptly destroyed it. Crook was taken to Milwaukee and charged in federal court the following Monday.

Few details were given about Crook's brewery in the newspaper reports published in the aftermath of the raid. Judging by the punishment, though, it seems the setup may have been fairly elaborate. In May 1930, Crook pleaded guilty and was given the standard $250 fine. Then the other shoe dropped. He was sentenced to serve six months in the House of Corrections in Milwaukee. For the 66-year-old Crook, it was practically a death sentence.

He had been in poor health for nearly a decade prior to being sent to jail. His time in a cage didn't help him any. He returned to Oshkosh in November of 1930. Days later he underwent an operation at Mercy Hospital for an undisclosed illness. Crook never fully recovered. He died at the Fowler House on March 6, 1931. Oshkosh Chief of Police Arthur Gabbert was among those who helped carry the former bootlegger to his grave. William J. Crook was 67 years old.

Burned Out

Lizzie and their son Cyrus kept the Fowler House going. They even managed to re-open the "soft drinks" parlor that Prohibition agents had shut down. And when Prohibition ended in 1933, that corner of the Fowler House became a proper tavern again with Cyrus Crook managing the bar.

Lizzie Crook continued to operate the Fowler House until 1946 when she sold the business and retired. She would remain in Oshkosh until her death in 1971 at the age of 98.

After Lizzie retired, the Fowler House Hotel morphed into a tavern and restaurant with apartments above. From 1947 until 1955 it was called the Town Grill. From 1956 until 1970 it was the Town House Inn.

It was the Coach House Inn from 1970 until 1972 when it became the Top Hat Bar for several months before the name was changed again in 1973 to Bobby McGee's. It would remain Bobby McGee's until 1980.

In 1980, the bar was renamed Bentley's. It became Garfield's in 1983 and Chez Joey's in 1985. Fire was almost as frequent as the name changes. This building hosted significant fires in 1897, 1927, 1930, 1970, and 1986.

The hotel Edwin Fowler built in 1876 was reduced to rubble by that one. The last remnant of the early Fowler House was the adjacent building where the hotel had maintained an additional set of rooms during the peak years of the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Last year, that went up in flames, too.

If William Crook were alive to see what is now the empty corner at High and Division, he'd have to wonder, what the hell happened here? It's all gone. There are a lot of places like this in Oshkosh. Paved over lots in old neighborhoods that beg that question... what the hell happened here?

|

| The southeast corner of High and Division streets, November 2019. |

The brewery is just a small part of the story of this place. That corner was once full of life. Its peculiar history dates back to the early 1870s.

The Fowler House Hotel

In the summer of 1870, an English-born cobbler named Edwin Fowler bought the property at the corner of what was then High and Light streets. In 1876, Fowler put up a building there that would stand for the next 110 years. It was a two-story, wooden structure encased in brick with a roof made of tin and iron. The image below is from the late 1940s. The exterior of Fowler's old building hadn't changed all that much in the intervening years.

|

| Circa 1948. |

For more than 70 years, that was known as the Fowler House Hotel. Its first keeper was William Perrin, an English immigrant who came to Oshkosh in 1850. Perrin worked in a sawmill before he went into the hospitality business as a steward on a steamboat. In the early 1860s, he went ashore to become a hotelier. He ran at least three other hotels in Oshkosh prior to opening the Fowler House on June 15, 1876. Perrin was the guy who built the template the Fowler House would follow for decades to come.

This was not the Athearn. The Fowler House was among the cheapest hotels in Oshkosh. A room could be had for a dollar a night; about $25 in today's money. With rates that low, Perrin had to sell more than just lodging to make a buck. The hotel's profit center was the saloon that squatted in the street-corner portion of the first floor.

The Fowler House became popular with what the Daily Northwestern referred to as "the country people." That meant farmers coming to Oshkosh to sell their hay, produce, and livestock; or just to get the hell off the farm and live it up for a little while in the wicked city. The Fowler House and the Commercial Hotel, located directly across Light Street (now Division), were twin beacons for these folks.

The Lay of the Land

That busy photo above was taken from behind the Commercial Hotel looking east towards the back of the Fowler House. The yellow circles halo Oshkosh Brewing Company beer signs. They hang from both the Commercial Hotel, in the foreground, and the Fowler House in the background. Immediately to the right of the Fowler House is an attached house that served as the hotel's kitchen. At the extreme right is a portion of the Fowler House barn where guests stabled their horses.

The map below is from 1889. It details the layout of the neighborhood surrounding the Fowler House.

The 1889 map also shows the expansion that took place at the Fowler House. By this time there were two-buildings: the original hotel at 67-69 High and the addition to it at 61-65 High. They were connected by a passageway that provided access to the 25 rooms on the second floor of the 61-65 High address. Just to the east at 57 High is now The Reptile Palace bar.

A Canadian from Michigan

William Perrin quit the Fowler House in 1894. The hotel closed a couple of years later. In 1897, while the building sat vacant, two fires almost demolished the place. Both fires were thought to have been set by arsonists. The second fire, in the wee hours of October 27, 1897, left three firefighters injured and the building nearly gutted.

The Fowler House was quickly repaired and was back in business the following year. Over the next few years, a series of keepers shuffled through until William Crook arrived in 1906. Crook’s tenure coincided with the hotel's most colorful period.

William J. Crook was born in Canada in 1863. But most of his early life was spent in and around Manistee, Michigan. He’d started working in the sawmills there while still in his teens. Crook appears to have become familiar with Oshkosh in the 1890s. If he was coming here to look for a wife, he’d come to the right place. In 1896, the 33-year-old Crook married a 24-year-old Oshkosh woman named Louisa Hakbarth. Bill and Lizzie moved to Seattle after their marriage, but by 1905 they had returned to Oshkosh.

Crook took a job running a ramshackle saloon at the tip of the v-shaped intersection of Jackson and Light (now Division) streets. The place was surrounded by industry. It had formerly been the city market where local farmers sold their goods.

|

| The City Market before it became Crook’s Saloon. |

Crook stayed there for just a year. He took a lease on the Fowler House in November of 1906. His first 13 years at the hotel were relatively serene. Crook mimicked Perrin’s successful run, offering cheap accommodations and plenty to drink.

But the Fowler House formula came undone when the Wartime Prohibition Act took effect in the summer of 1919. That was followed by National Prohibition in 1920. Crook closed the bar at the Fowler House. He attempted to make up for the lost revenue by diversifying. He opened a tire sales and repair shop in the barn behind the hotel. The offices of Crook Tire Co. took over the space that had formerly been occupied by the hotel’s saloon.

|

| Looking north towards High Avenue from Division Street in 1920. Photo courtesy of Dan Radig. |

The tire business wasn’t enough. Crook added another revenue stream; a Yellow Cab Company that he based out of the hotel. In Oshkosh, this sort of entrepreneurship was not how most bar owners responded to the dry law.

Crook’s Dilemma

When Prohibition arrived, the majority of the city’s saloon keepers immediately converted their bars into speakeasies. But for Crook, that option entailed more than just the risk of arrest. Crook didn't own the Fowler House, he was leasing it. If he were to get busted on a dry-law violation he stood the chance of losing not only his lease and livelihood, but the roof over his head. Bill and Lizzie Crook and their son Cyrus all lived at the hotel.

But operating within the law was hardly more appealing. The hotel was within walking distance of at least 10 former saloons that had become speakeasies. All that business was being drained away. It finally became more than Crook could take.

In 1925, he ended his lease on the Fowler House and purchased the property outright. Shortly after, Crook moved the tire company office out of the corner space and put the saloon back in. Of course, he couldn’t call it a saloon. His license said it was a soft-drinks parlor. It was anything but.

Crook wasn’t at all tentative in his new endeavor. When he began violating the dry law he seems to have done so with a flagrancy that was uncommon even in sodden Oshkosh.

The Fowler House speakeasy had soon caught the attention of local authorities. Crook’s bar was being investigated by Frank Keefe of the Winnebago County District Attorney's Office. Normally, the county DA didn’t like to get involved in the affairs of Oshkosh’s thriving bootleg beer and liquor scene. Here was an exception. Crook was not only selling liquor over his bar he was also retailing bottled booze for carryout. Keefe later alleged that those violations were compounded by the bar's popularity with an underage clientele.

On May 14, 1928, the Fowler House was raided. Crook managed to avoid arrest. Emil Harder, a Swiss immigrant who co-managed the bar with Armin Meister, was taken into custody. Harder was slapped with a $250 fine; about $4,000 in today's money. He also lost his job after he promised the judge he'd go straight and never do anything like it again. Crook had no intention of quitting. He hired Herman Priebe to be his new bar manager and re-opened the saloon. Then he upped the ante.

A wildcat brewery was installed in the basement of the Fowler House. Crook had no experience making beer. None was needed. The brewery was almost certainly a partnership with one of the local beer bootleggers operating in Oshkosh during this time. It would have been a standard arrangement: Crook supplies the space, the bootlegger supplies everything else. And the money comes rolling in.

It was a bold, perhaps foolhardy, move for the owner of an establishment already under the scrutiny of law enforcement. Crook had to have known he was pushing his luck. He couldn't have been too surprised by the result.

The Fowler House was raided again on the Saturday afternoon of February 22, 1930. This time it was federal agents who busted in. And this time, Crook was arrested. The feds found beer and whiskey at the bar. They found the brewery in the basement and promptly destroyed it. Crook was taken to Milwaukee and charged in federal court the following Monday.

Few details were given about Crook's brewery in the newspaper reports published in the aftermath of the raid. Judging by the punishment, though, it seems the setup may have been fairly elaborate. In May 1930, Crook pleaded guilty and was given the standard $250 fine. Then the other shoe dropped. He was sentenced to serve six months in the House of Corrections in Milwaukee. For the 66-year-old Crook, it was practically a death sentence.

He had been in poor health for nearly a decade prior to being sent to jail. His time in a cage didn't help him any. He returned to Oshkosh in November of 1930. Days later he underwent an operation at Mercy Hospital for an undisclosed illness. Crook never fully recovered. He died at the Fowler House on March 6, 1931. Oshkosh Chief of Police Arthur Gabbert was among those who helped carry the former bootlegger to his grave. William J. Crook was 67 years old.

|

| William Crook’s headstone in Riverside Cemetery, Oshkosh. |

Burned Out

Lizzie and their son Cyrus kept the Fowler House going. They even managed to re-open the "soft drinks" parlor that Prohibition agents had shut down. And when Prohibition ended in 1933, that corner of the Fowler House became a proper tavern again with Cyrus Crook managing the bar.

Lizzie Crook continued to operate the Fowler House until 1946 when she sold the business and retired. She would remain in Oshkosh until her death in 1971 at the age of 98.

After Lizzie retired, the Fowler House Hotel morphed into a tavern and restaurant with apartments above. From 1947 until 1955 it was called the Town Grill. From 1956 until 1970 it was the Town House Inn.

It was the Coach House Inn from 1970 until 1972 when it became the Top Hat Bar for several months before the name was changed again in 1973 to Bobby McGee's. It would remain Bobby McGee's until 1980.

|

| Oshkosh Advance-Titan, October 12, 1978. |

In 1980, the bar was renamed Bentley's. It became Garfield's in 1983 and Chez Joey's in 1985. Fire was almost as frequent as the name changes. This building hosted significant fires in 1897, 1927, 1930, 1970, and 1986.

|

| The fire of January 26, 1986. |

The hotel Edwin Fowler built in 1876 was reduced to rubble by that one. The last remnant of the early Fowler House was the adjacent building where the hotel had maintained an additional set of rooms during the peak years of the late 1800s and early 1900s.

|

| The former east wing of the Fowler House in gold and grey. |

Last year, that went up in flames, too.

|

| November 24th 2018. |

If William Crook were alive to see what is now the empty corner at High and Division, he'd have to wonder, what the hell happened here? It's all gone. There are a lot of places like this in Oshkosh. Paved over lots in old neighborhoods that beg that question... what the hell happened here?

Friday, November 15, 2019

Bruehmueller’s Old Saloon

Here's a clipping from 1902 when Frank Bruehmueller’s saloon was located kitty corner from the Wisconsin Central Railway Depot on 9th.

Bruehmueller’s beer garden was on the east side of the building. His old saloon still stands. Today, it’s Andy's Pub & Grub at 527 W. 9th Ave.

Bruehmueller’s beer garden was on the east side of the building. His old saloon still stands. Today, it’s Andy's Pub & Grub at 527 W. 9th Ave.

|

| Looking towards the East side of Andy's where Bruehmueller’s Beer Garden had been. |

Tuesday, November 12, 2019

Holiday Beer is Near

Just a quick note that this past weekend, Jody Cleveland of Bare Bones Brewery and I made a 7-barrel batch using the 1950s recipe for Chief Oshkosh Holiday Beer from the Oshkosh Brewing Company. It should be ready in time for Christmas. I’ll send a shout out when it's available….

Thursday, November 7, 2019

There's a Barrel-Aging Program Underway at Fifth Ward

Fifth Ward Brewing will release its first barrel-aged beers this Saturday, November 9th as part of the brewery's second-anniversary celebration. The line-up includes four beers aged in bourbon barrels. Three of those beers have been conditioned on different sets of ingredients (see the bottom of this post for descriptions). This is just the first glimpse of something Ian Wenger and Zach Clark of Fifth Ward have been working towards since their brewery opened in 2017.

The four bourbon barrel-aged beers began with an imperial stout. "We brewed that back in April and it went into barrels on May 12," Wenger said. "It was my sister's birthday, that's why I remember that. In the past two months, we’ve filled three more barrels. We have a rye whiskey barrel of Buffalo Plaid (a strong, Scotch ale brewed with maple syrup), a rye whiskey or Burl Brown Ale, and a bourbon barrel of Hades Secret (an imperial porter brewed with chocolate and mint)."

Those beers won’t see the light of day for months. The long road to release is an expensive way for a small brewery to operate. "We're learning how we go about financing this," Clark says. "It's a big investment. Right now we have $2,000 in raw materials and $1,500 in barrels that we're just sitting on."

They're also sitting on something that pre-dates the 2017 opening of the brewery. Fifth Ward's barrel program includes a beer they're calling Real Wild Sour. That beer will also make its debut at the anniversary party on Saturday. It began as a blonde ale that underwent secondary fermentation in an oak barrel spiked with a mixed culture of yeast and bacteria.

"This is a culture we've been building for 4 years," says Clark. "I started collecting and then building up and blending these various cultures in carboys. We have two other carboys going, but I think this is our best blend. We're going to go a lot deeper into this as we grow our sour program. We'll use that blend in addition to some lab-grade stuff, but this blend is the basis of the program."

Barrel-aged and mixed-fermentation beer isn't new to Oshkosh, but this is the first time a brewery here has taken such a structured, long-term approach to it. It seems like the next logical step for a brewery that, from the start, has been intent on continually expanding the range of beers it produces. As Clark says, “We want variety here. We want creativity.”

Below are the bourbon-barrel beer variants being released at Fifth Ward this Saturday.

BOURBON BARREL TWO MAN JOB (Limited Tap & Limited Bottles)

Bourbon Barrel Aged Imperial Oatmeal Stout.

BOURBON BARREL S'MORES JOB (Tap & Bottles)

Bourbon Barrel Aged Imperial Oatmeal Stout conditioned on Graham Cracker, Cocoa Nibs, and Vanilla Paste.

BOURBON BARREL NUT JOB (Limited Tap & Limited Bottles)

Bourbon Barrel Aged Imperial Oatmeal Stout conditioned on Coconut and Pecans.

BOURBON BARREL CAFE JOB (Limited Tap & Limited Bottles)

Bourbon Barrel Aged Imperial Oatmeal Stout conditioned on Fresh House Roasted Coffee Beans

|

| Ian Wenger (left) and Zach Clark with their barrels. |

The four bourbon barrel-aged beers began with an imperial stout. "We brewed that back in April and it went into barrels on May 12," Wenger said. "It was my sister's birthday, that's why I remember that. In the past two months, we’ve filled three more barrels. We have a rye whiskey barrel of Buffalo Plaid (a strong, Scotch ale brewed with maple syrup), a rye whiskey or Burl Brown Ale, and a bourbon barrel of Hades Secret (an imperial porter brewed with chocolate and mint)."

Those beers won’t see the light of day for months. The long road to release is an expensive way for a small brewery to operate. "We're learning how we go about financing this," Clark says. "It's a big investment. Right now we have $2,000 in raw materials and $1,500 in barrels that we're just sitting on."

They're also sitting on something that pre-dates the 2017 opening of the brewery. Fifth Ward's barrel program includes a beer they're calling Real Wild Sour. That beer will also make its debut at the anniversary party on Saturday. It began as a blonde ale that underwent secondary fermentation in an oak barrel spiked with a mixed culture of yeast and bacteria.

"This is a culture we've been building for 4 years," says Clark. "I started collecting and then building up and blending these various cultures in carboys. We have two other carboys going, but I think this is our best blend. We're going to go a lot deeper into this as we grow our sour program. We'll use that blend in addition to some lab-grade stuff, but this blend is the basis of the program."

Barrel-aged and mixed-fermentation beer isn't new to Oshkosh, but this is the first time a brewery here has taken such a structured, long-term approach to it. It seems like the next logical step for a brewery that, from the start, has been intent on continually expanding the range of beers it produces. As Clark says, “We want variety here. We want creativity.”

Below are the bourbon-barrel beer variants being released at Fifth Ward this Saturday.

BOURBON BARREL TWO MAN JOB (Limited Tap & Limited Bottles)

Bourbon Barrel Aged Imperial Oatmeal Stout.

BOURBON BARREL S'MORES JOB (Tap & Bottles)

Bourbon Barrel Aged Imperial Oatmeal Stout conditioned on Graham Cracker, Cocoa Nibs, and Vanilla Paste.

BOURBON BARREL NUT JOB (Limited Tap & Limited Bottles)

Bourbon Barrel Aged Imperial Oatmeal Stout conditioned on Coconut and Pecans.

BOURBON BARREL CAFE JOB (Limited Tap & Limited Bottles)

Bourbon Barrel Aged Imperial Oatmeal Stout conditioned on Fresh House Roasted Coffee Beans

Tuesday, November 5, 2019

Fifth Ward Heading Into Year Three

This coming Saturday, November 9th, Fifth Ward Brewing in Oshkosh celebrates its second anniversary with all the trimmings: a bunch of new beer releases, live music, food trucks. I'll have more on the beer side of things later this week, but in the meantime, Fifth Ward has posted a nice rundown of the event at the brewery's 2nd Anniversary Facebook event page.

All of which gives me a good excuse to trot out a few pictures I've been collecting. Ian Wenger and Zach Clark opened the doors at Fifth Ward on the Friday afternoon of October 20, 2017. The brewery's grand opening was held on November 12. That evening I took this shot of Ian and Zach behind their bar in front of the taps.

Last year Fifth Ward celebrated its first anniversary with a party on Saturday, November 10. I dropped by Fifth Ward a couple of days earlier. Zach and Ian were there behind the bar again. I was reminded of the picture from 2017. I thought it would be good to get an updated photo. Here's that picture from November 7, 2018.

A couple of weeks ago I was at Fifth Ward talking with Zach and Ian and I cajoled them into getting their pictures taken again as they head into year three. Here's the 2019 edition...

They're holding up pretty well! Congratulations Ian and Zach, hope there are many more of these to come.

All of which gives me a good excuse to trot out a few pictures I've been collecting. Ian Wenger and Zach Clark opened the doors at Fifth Ward on the Friday afternoon of October 20, 2017. The brewery's grand opening was held on November 12. That evening I took this shot of Ian and Zach behind their bar in front of the taps.

|

| Ian Wenger (left) and Zach Clark, 2017. |

Last year Fifth Ward celebrated its first anniversary with a party on Saturday, November 10. I dropped by Fifth Ward a couple of days earlier. Zach and Ian were there behind the bar again. I was reminded of the picture from 2017. I thought it would be good to get an updated photo. Here's that picture from November 7, 2018.

|

| 2018. |

A couple of weeks ago I was at Fifth Ward talking with Zach and Ian and I cajoled them into getting their pictures taken again as they head into year three. Here's the 2019 edition...

|

| 2019. |

They're holding up pretty well! Congratulations Ian and Zach, hope there are many more of these to come.

Monday, November 4, 2019

Leonard Arnold and His Unusual Brewery

Once upon a time, there was a small brewery on the east side of South Main Street in Oshkosh. Here's what that site looks like today.

Leonard G. Arnold made beer there from 1875 until about 1879. His brewery was like no other in Oshkosh.

Arnold wasn't your typical Oshkosh brewery owner. Prior to launching his brewery, he had no previous brewing experience. He was born in Milwaukee in 1845. His parents, Frederick and Barbara, had emigrated from Bavaria in the late 1830s. They were married in Cleveland where they had the first of their nine children in 1841. A couple of years later, they relocated to Milwaukee. In 1851, the Arnold clan moved to Oshkosh and began putting down roots.

Frederick Arnold bought land at the northwest corner of what is now Bay Shore and Frankfort streets and proceeded to build a house there for his growing family. The home Leonard Arnold grew up in still stands. It’s about 165 years old.

Leonard Arnold spent his youth working as a butcher. He had learned the trade from his father. In early adulthood he began roaming. He lived for a while in Chicago. Then Nashville. And then Manhattan, Kansas. He supported himself by sometimes working as a butcher and at other times working for railroad companies. Arnold was 20 in 1865 when he moved back to Wisconsin.

He settled in Fond du Lac. There he opened a meat market with his older brother Joseph, a Civil War veteran. Joseph had recently been released from a POW camp. He had been taken prisoner in 1863 at the Battle of Gettysburg.

The Arnold brother’s Fond du Lac meat market folded in 1872. Both Leonard and Joseph returned to Oshkosh. And this is when Leonard Arnold's drift towards beer begins.

Back in Oshkosh, Leonard Arnold partnered with August Fugleberg. Together they purchased the Northwestern Vinegar Works from John Young. Allow me yet another digression. Young had sold off his vinegar works because he was about to start working for Philip Best Brewing of Milwaukee. This would later become Pabst Brewing. Young’s job was to distribute the brewery’s beer in Oshkosh.

OK, let’s get back to Leonard Arnold. The vinegar works he and Fugleberg acquired from Young was located between Doty and South Main streets just below 19th Avenue. That land is now part of Fugleberg Park. The clipping that follows is from an 1873 map of Oshkosh that lists the different types of vinegar produced by Fugleberg and Arnold.

The Fugleberg/Arnold partnership soon fell apart. At the end of 1874, Leonard Arnold moved on. Fugleberg stayed on. The Fugleberg Park vinegar plant would remain in operation into the early 1900s. There's a marker in Fugleberg Park that mentions the old vinegar factory that once stood there.

After splitting with Fugleberg, Leonard Arnold took his newly acquired skills up the road. On March 11, 1875, he purchased a pair of lots at what is now 1600 South Main Street. He began building his own vinegar plant there. It was just three blocks up from the older Fugleberg facility.

The primary building was two-stories, wood-framed and veneered with brick. Inside an attached structure, Arnold drilled down and tapped an artesian well that supplied the water tank he used to capture his brewing water. He also constructed an ice house adjacent to what was about to become his brewery.

There are several fire insurance maps that show the configuration of the Arnold’s brewery. The best of them is from 1890. This was made a decade after Leonard Arnold had stopped brewing beer, but the basic make-up of the facility had remained unchanged. Here's that 1890 map.

Arnold's brewery went up in an area that had become Oshkosh's prime corridor for beer production and packaging. Across the street was Horn and Schwalm's Brooklyn Brewery. Further south along Doty were two white beer breweries and two beer bottling plants. At the end of the street was Glatz and Elser's Union Brewery, at the time the largest brewery in Oshkosh.

By June 1875, Arnold had his brewery up and running. Vinegar was his original concern, but he was soon turning out beer as well. The connection between vinegar and beer brewing was not at all uncommon. The manufacturing processes are similar and have a long tradition of being paired. Arnold wasn't the only brewer in Winnebago County to produce beer and vinegar in tandem. Fritz Bogk in Butte des Morts was doing that, too. But Arnold added his own twist. He made spruce beer.

Prior to 1875, spruce beer was rarely seen in Oshkosh. It was, however, quite common in other parts of the region and especially so in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. Arnold may have been drinking it in the late 1860s when he was living in Fond du Lac. At that time, Hiram Eaton's Spruce Beer Brewery was doing well there. Perhaps Arnold saw an untapped market for it in Oshkosh.

Spruce beers of this period were low in alcohol, typically less than 3% ABV. It's not known how Arnold formulated his recipe, but spruce tips or essence would probably have been the main flavoring component. Molasses and brown sugar were commonly used ingredients. Some spruce beers were brewed with hops. Arnold had a mash tun in his facility, so it's possible he was using a grist that included malted barley. Regardless of what Arnold was up to on that front, it appears he soon moved beyond the production of the spruce beers, lemon beers, and ginger beers that constituted his earliest efforts.

In the fall of 1875, Arnold advertised that he was now producing a standard beer. Below is an ad from the Wisconsin Telegraph, a German-language newspaper published in Oshkosh.

Here's my clumsy translation:

Vinegar and beer I can see, but ink? It didn't take much digging to discover that it makes sense. Vinegar was commonly used in the production of ink, as was beer; though to a lesser extent. The "7 Main Street" address where orders could be left was home to a restaurant. It was run by the one and only Joseph Arnold, whom we met earlier. The image below is from 1875 and shows Joseph Arnold’s restaurant. The red arrow beneath the sign for "REFRESHMENTS" indicates 7 Main, the place to place orders for Arnold's beer.

Arnold's beer production raises more questions than answers. He began at a time when bottled beer was becoming more common in Oshkosh. His spruce beer, which would not have been the sort of beer most saloon keepers would have put on tap, would have been an ideal candidate for bottling. But I’ve yet to find anything confirming that Arnold bottled his spruce beer.

Arnold's standard beer remains similarly elusive. What sort of beer was this? That question hovers over most of the beer from this period. It's only in the latter part of the 1870s that we begin to see Oshkosh brewers identifying their beers by style or type. Before this, it was all just beer. Or in Arnold's case, Bier.

Arnold's brewery is made more obscure by the fact that it lasted for such a short time. His beer brewing appears to have ended by late 1878 or early 1879. By 1880 he had moved to Menasha where he was living with his younger sister Lilly. He had gone into the candy making business.

In 1881, Leonard Arnold sold the property at 1600 South Main to his younger brother George. George kept the place going producing vinegar and yeast well into the 1930s. Leonard Arnold served as the vice-president of that business into the 1900s. But he doesn't seem to have had much to do with its daily operations.

In 1885, while still living in Menasha, the 40-year-old Arnold married a 26-year-old Oshkosh woman named Minnie Arnold. She was the daughter of early Oshkosh settler Johann Sixtus Arnold. But despite sharing a last name, the two of them appear not to have been related.

Minnie died of a lung disease two years after their marriage.

Leonard Arnold died in Los Angeles in 1919. He was 73 years old. His body was brought back to Oshkosh. He’s buried in Riverside Cemetery next to his parents in the Arnold family plot.

|

| 1600 South Main Street |

Leonard G. Arnold made beer there from 1875 until about 1879. His brewery was like no other in Oshkosh.

Arnold wasn't your typical Oshkosh brewery owner. Prior to launching his brewery, he had no previous brewing experience. He was born in Milwaukee in 1845. His parents, Frederick and Barbara, had emigrated from Bavaria in the late 1830s. They were married in Cleveland where they had the first of their nine children in 1841. A couple of years later, they relocated to Milwaukee. In 1851, the Arnold clan moved to Oshkosh and began putting down roots.

Frederick Arnold bought land at the northwest corner of what is now Bay Shore and Frankfort streets and proceeded to build a house there for his growing family. The home Leonard Arnold grew up in still stands. It’s about 165 years old.

|

| 1124 Bay Shore Drive. |

Leonard Arnold spent his youth working as a butcher. He had learned the trade from his father. In early adulthood he began roaming. He lived for a while in Chicago. Then Nashville. And then Manhattan, Kansas. He supported himself by sometimes working as a butcher and at other times working for railroad companies. Arnold was 20 in 1865 when he moved back to Wisconsin.

He settled in Fond du Lac. There he opened a meat market with his older brother Joseph, a Civil War veteran. Joseph had recently been released from a POW camp. He had been taken prisoner in 1863 at the Battle of Gettysburg.

|

| A drawing of Joseph Arnold, circa 1897. |

The Arnold brother’s Fond du Lac meat market folded in 1872. Both Leonard and Joseph returned to Oshkosh. And this is when Leonard Arnold's drift towards beer begins.

Back in Oshkosh, Leonard Arnold partnered with August Fugleberg. Together they purchased the Northwestern Vinegar Works from John Young. Allow me yet another digression. Young had sold off his vinegar works because he was about to start working for Philip Best Brewing of Milwaukee. This would later become Pabst Brewing. Young’s job was to distribute the brewery’s beer in Oshkosh.

|

| Oshkosh City Directory, 1876. |

OK, let’s get back to Leonard Arnold. The vinegar works he and Fugleberg acquired from Young was located between Doty and South Main streets just below 19th Avenue. That land is now part of Fugleberg Park. The clipping that follows is from an 1873 map of Oshkosh that lists the different types of vinegar produced by Fugleberg and Arnold.

The Fugleberg/Arnold partnership soon fell apart. At the end of 1874, Leonard Arnold moved on. Fugleberg stayed on. The Fugleberg Park vinegar plant would remain in operation into the early 1900s. There's a marker in Fugleberg Park that mentions the old vinegar factory that once stood there.

|

| Fugleberg Park |

After splitting with Fugleberg, Leonard Arnold took his newly acquired skills up the road. On March 11, 1875, he purchased a pair of lots at what is now 1600 South Main Street. He began building his own vinegar plant there. It was just three blocks up from the older Fugleberg facility.

The primary building was two-stories, wood-framed and veneered with brick. Inside an attached structure, Arnold drilled down and tapped an artesian well that supplied the water tank he used to capture his brewing water. He also constructed an ice house adjacent to what was about to become his brewery.

There are several fire insurance maps that show the configuration of the Arnold’s brewery. The best of them is from 1890. This was made a decade after Leonard Arnold had stopped brewing beer, but the basic make-up of the facility had remained unchanged. Here's that 1890 map.

Arnold's brewery went up in an area that had become Oshkosh's prime corridor for beer production and packaging. Across the street was Horn and Schwalm's Brooklyn Brewery. Further south along Doty were two white beer breweries and two beer bottling plants. At the end of the street was Glatz and Elser's Union Brewery, at the time the largest brewery in Oshkosh.

By June 1875, Arnold had his brewery up and running. Vinegar was his original concern, but he was soon turning out beer as well. The connection between vinegar and beer brewing was not at all uncommon. The manufacturing processes are similar and have a long tradition of being paired. Arnold wasn't the only brewer in Winnebago County to produce beer and vinegar in tandem. Fritz Bogk in Butte des Morts was doing that, too. But Arnold added his own twist. He made spruce beer.

Prior to 1875, spruce beer was rarely seen in Oshkosh. It was, however, quite common in other parts of the region and especially so in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. Arnold may have been drinking it in the late 1860s when he was living in Fond du Lac. At that time, Hiram Eaton's Spruce Beer Brewery was doing well there. Perhaps Arnold saw an untapped market for it in Oshkosh.

Spruce beers of this period were low in alcohol, typically less than 3% ABV. It's not known how Arnold formulated his recipe, but spruce tips or essence would probably have been the main flavoring component. Molasses and brown sugar were commonly used ingredients. Some spruce beers were brewed with hops. Arnold had a mash tun in his facility, so it's possible he was using a grist that included malted barley. Regardless of what Arnold was up to on that front, it appears he soon moved beyond the production of the spruce beers, lemon beers, and ginger beers that constituted his earliest efforts.

In the fall of 1875, Arnold advertised that he was now producing a standard beer. Below is an ad from the Wisconsin Telegraph, a German-language newspaper published in Oshkosh.

Here's my clumsy translation:

L.G. Arnold

Manufacturer of

Vinegar, Ink and Beer

Building located at 16 Kansas Street

Post Office Box 176 - Oshkosh, WI

Orders can be left at 7 Main Street

Vinegar and beer I can see, but ink? It didn't take much digging to discover that it makes sense. Vinegar was commonly used in the production of ink, as was beer; though to a lesser extent. The "7 Main Street" address where orders could be left was home to a restaurant. It was run by the one and only Joseph Arnold, whom we met earlier. The image below is from 1875 and shows Joseph Arnold’s restaurant. The red arrow beneath the sign for "REFRESHMENTS" indicates 7 Main, the place to place orders for Arnold's beer.

Arnold's beer production raises more questions than answers. He began at a time when bottled beer was becoming more common in Oshkosh. His spruce beer, which would not have been the sort of beer most saloon keepers would have put on tap, would have been an ideal candidate for bottling. But I’ve yet to find anything confirming that Arnold bottled his spruce beer.

Arnold's standard beer remains similarly elusive. What sort of beer was this? That question hovers over most of the beer from this period. It's only in the latter part of the 1870s that we begin to see Oshkosh brewers identifying their beers by style or type. Before this, it was all just beer. Or in Arnold's case, Bier.

Arnold's brewery is made more obscure by the fact that it lasted for such a short time. His beer brewing appears to have ended by late 1878 or early 1879. By 1880 he had moved to Menasha where he was living with his younger sister Lilly. He had gone into the candy making business.

In 1881, Leonard Arnold sold the property at 1600 South Main to his younger brother George. George kept the place going producing vinegar and yeast well into the 1930s. Leonard Arnold served as the vice-president of that business into the 1900s. But he doesn't seem to have had much to do with its daily operations.

In 1885, while still living in Menasha, the 40-year-old Arnold married a 26-year-old Oshkosh woman named Minnie Arnold. She was the daughter of early Oshkosh settler Johann Sixtus Arnold. But despite sharing a last name, the two of them appear not to have been related.

|

| Minnie Arnold. |

Minnie died of a lung disease two years after their marriage.

Leonard Arnold died in Los Angeles in 1919. He was 73 years old. His body was brought back to Oshkosh. He’s buried in Riverside Cemetery next to his parents in the Arnold family plot.

|

| Leonard G. Arnold 1845-1919. |