|

| John Glatz |

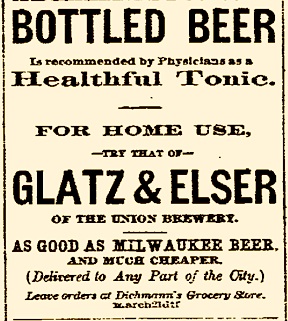

The type of barley (6-row) that grew so well in Winnebago County had a downside when it came to producing beer. Its high-protein content tended to result in a beer that was more prone to haze and spoilage over time. That wasn't overly problematic for Glatz when all of his beer was going into kegs that were soon enough drained in local saloons. But now that it was being bottled, brewing a more durable beer became a more pressing concern. It was a problem facing many American brewers of the period. Within easy reach was a ready solution: corn.

An addition of corn to the mash, typically about 20% of the grain bill, corrected the issues caused by protein-rich American barley. It became a staple in the development of American-style lagers and was a practice embraced by brewers in Oshkosh. Glatz, in fact, may have been the first brewer here to introduce corn as an ingredient in his beer.

The widespread use of adjuncts such as corn or rice by American lager breweries began in earnest in the 1870s. The chief proponent of the idea was Anton Schwarz, a Bohemian born brewing scientist who immigrated to America in 1868. After his arrival, articles by Schwarz promoting the use of adjuncts began appearing in The American Brewer, the first trade journal specifically addressing brewers in the United States. Schwarz’s writings were highly influential. Whether or not Glatz was reading them isn’t known, but he was certainly in contact with brewers who were.

Glatz had come to Oshkosh from Milwaukee where he had spent the previous 12 years brewing beer at C.T. Melms South Side Brewery, then among the largest breweries of that city. After moving to Oshkosh, Glatz maintained his connections to brewers in Milwaukee and would have been well aware of the changes occurring there. In the 1870s, corn was gradually becoming accepted by Milwaukee brewers for the host of benefits it conveyed. Not least among them was cost. It’s unlikely this escaped the attention of Glatz.

In Winnebago County, corn was grown in abundance and available at a fraction of the cost of malted barley. For Glatz, it would have presented an irresistible option. Not only did corn make his beer more shelf stable, it made the beer cheaper to produce. But corn also impacted the flavor. It lightened the beer’s body and color.

That may not have been seen as a benefit to an old-school German brewer like Glatz, who was weaned on the all-malt brews of his homeland. His customer’s in Oshkosh, though, loved it. At the close of the 1870s, Glatz’s brewery had grown into the largest here, producing more than 1,600 barrels of beer annually.

By the late 1880s corn was being used extensively by brewers in Oshkosh. Glatz used corn grits – milled corn with the outer shell and oily germ of the kernal removed. At Horn and Schwalm’s Brooklyn Brewery, corn grits were also the standard. The Rahr Brewing Company came to favor flaked corn. And at Lorenz Kuenzl's Gambrinus Brewery, corn meal was used.

Kuenzl's use of adjuncts is instructive. He brewed with both corn meal and rice at the Gambrinus Brewery. These ingredients were far more costly than the malt he used. For example, an 1892 inventory of the Gambrinus Brewery shows the malt on hand valued at 60 cents per pound. Corn meal was $1.00 per pound, while rice was $2.75 per pound. Cleary, the use of such materials wasn't just a matter of price for brewers like Kuenzl. It was a method for achieving specific qualities within the beer. In fact, American beers from this period brewed with corn or rice were regularly sweeping international competitions.

Kuenzl's use of adjuncts is instructive. He brewed with both corn meal and rice at the Gambrinus Brewery. These ingredients were far more costly than the malt he used. For example, an 1892 inventory of the Gambrinus Brewery shows the malt on hand valued at 60 cents per pound. Corn meal was $1.00 per pound, while rice was $2.75 per pound. Cleary, the use of such materials wasn't just a matter of price for brewers like Kuenzl. It was a method for achieving specific qualities within the beer. In fact, American beers from this period brewed with corn or rice were regularly sweeping international competitions.But what began as a boon grew into a bane over time. The American lagers of the late 1800s brewed with corn or rice share only a passing resemblance to the mass market adjunct lagers that are pervasive today. The degeneration of these beers played out over generations and at least one Oshkosh brewer succumbed to the regressive trend.

After David Uihlein purchased the Oshkosh Brewing Company in 1961, the brewery abandoned the corn grits that had been used in OBC's beer since 1894. Replacing it was something called NU-BRU, a corn syrup created with brewers in mind. A full 30% of the fermentable materials used in the Chief Oshkosh Lager of the 1960s came from this gooey concoction. The syrup may have streamlined the brewing process, but it didn't appear to help the beer any. Sales of Chief Oshkosh went into a long and, for the brewery, fatal slide after the introduction of the new ingredient.

|

| Happy Tail Cream Ale |

More recently, Bare Bones Brewery has used corn in its Happy Tail Cream Ale. "I only use a small amount for sweetness that only corn can give," says Bare Bones brewmaster Lyle Hari. "Not for a filler but to keep the beer in style and add that corn like sweetness it should have."

Hari's approach is typical of craft brewers today who most often reserve their use of corn for brewing classic styles that require it. For American style dark lagers, pilseners and cream ales it's an essential element.

In Oshkosh, we've been brewing with corn for close to 140 years. It's an ingredient every bit as traditional as malt, hops and yeast.

No comments:

Post a Comment