The good folks at Venture Wisconsin were nice enough to invite me on their show last night and allow me to talk (endlessly) about beer and brewing in Oshkosh past and present. We covered a lot of ground. You can find the video HERE.

Tuesday, July 30, 2019

Monday, July 29, 2019

When Tuff Brewed Peoples

His full name was George Alton Boeder. Nobody called him that. They called him Tuffy. Or just Tuff.

Tuff Boeder was born in Oshkosh on January 15, 1914. He was second-generation American. His grandfather Friedrich Böder had come to the U.S. in 1880 from Pommern, which was then a province of Germany. Tuff lived all his life in Oshkosh. He grew up in a modest home on the east side of town, at what is now 1003 School Avenue. His boyhood home still stands.

His father, Paul Boeder, was already working in the beer business when Tuff was born. Paul had started as a bookkeeper at the Schlitz distribution house on Division Street in Oshkosh in 1911. At that time, Schlitz was trying to claw its way back to prominence in the Oshkosh market. The brewery had struggled here for much of the previous decade thanks, in large part, to the rising fortunes of the Oshkosh Brewing Company.

That campaign had little success here. Schlitz finally gave up on Oshkosh and closed its branch here in 1918. Paul Boeder found a new job on the southside keeping the books for Peoples Brewing. He was there when Prohibition hit in 1920. The brewery quit making beer and started selling soda, fruit juice, near beer, malt tonics…

Prohibition ended in 1933. Peoples Brewing immediately went back to making real beer. Paul Boeder got Tuff a job there in 1936. Tuff married Ruth Pratsch that same year. He was 22 then. He’d come of age during the Great Depression when work in Oshkosh was hard to find. This was his first real job. He started out at Peoples putting labels on bottles.

“A lot was done by hand back then,” Tuff said. “We had to label each bottle separately. If we did 30 barrels a day that was a lot.”

Tuff moved up the ranks. In the early 1940s he began working as a route driver delivering Würtzer Beer and Old Derby Ale to local taverns and beer depots. He made $34 a week. Most of his stops were in and around town. Peoples had little need for wider distribution. The brewery was already growing at a good clip. Between 1943 and 1953 sales increased by 200 percent. “The taverns in Oshkosh wouldn’t buy that Milwaukee beer as long as Oshkosh had its own breweries,” Tuff said.

About 1951, Tuff moved back into the brewery. He went to work in the bottling department. Now he was making almost $55 for a 40-hour week. The days of hand labeling bottles were over. It had been automated. On a good day, that line could put out 50,000 bottles of beer.

In 1953, Tuff moved over to the brewhouse and began working as a brewer. He and Wilhelm Kohlhoff became the two principal brewers at Peoples. Kohlhoff had just started at the brewery. He was from Pommern, Germany; like Tuff’s family. The two of them became fast friends.

The brewmaster then was Dale Schoenrock. He had been with Peoples since 1940. Schoenrock was all business when it came to making beer.

"I’d get to work at three in the morning and start heating up the mash tub," Tuff said. "The temperature was critical. If the brewmaster said 56.5 degrees Celsius, he didn’t mean 56 or 57."

In 1956, Tuff was named Assistant Brewmaster. The work wasn't much different, but the pay was better. By 1957, he was making $73.40 a week. Tuff and Kohlhoff worked in shifts, turning out two or three batches of beer a day. The brewery was producing over 30,000 barrels of lager beer a year at this point.

"We used gravity to move the beer," Tuff said. "There were four floors. When it hit bottom it was done." At least Tuff's part was done. From there it went to the beer cellars for fermentation. "The brew would ferment for eight or nine days," he said. "It’s really going strong on day two. As it ferments, it gives off carbon dioxide gas and we’d collect and store this gas in huge tanks. Later on, this gas goes back into the beer (to carbonate it)."

Peoples had its own powerhouse and Tuff always worried that the massive steam generator would give out while he was brewing. It happened more than once. He had to "baby" those batches to completion. "If you lost your steam you could lose a brew," Tuff said. “That’s $5,000 down the drain. I never ruined a brew as long as I worked there."

Tuff told an incredible story that I can't verify. He said there was a period (presumably in the 1950s) when the Stroh Brewery of Detroit was making beer at Peoples. "They were having all kinds of trouble with their equipment, so we brewed it for them," Tuff said. "There were semis here, one right after the other picking up the beer. They gave us a recipe so we could match the flavor, but it wasn’t THE recipe. That’s always a secret."

There has to be more to this. When Tuff was brewing at Peoples, the Stroh Brewery was selling far more beer than Peoples was capable of making. By 1957 Stroh's annual output was 2.7 million barrels. The capacity of the Peoples brewery was well under 100,000 barrels annually. That said, the Stroh Brewery was shut down for 45-days by a strike in 1958. Perhaps Tuff’s recollections are in some way connected to that event. That’s just speculation, though.

Tuff worked in the brewhouse until the very end, 1972, when Peoples went bankrupt and closed. Theodore Mack was running Peoples then. Mack had come from Milwaukee where he had worked at Pabst. Tuff said that Mack offered to help him get a job at Pabst after Peoples shut down. Tuff didn’t want it. He didn’t want to move to Milwaukee. “I was getting too old,” he said. “Too close to retirement.”

Tuff had 36 years in at Peoples when the brewery failed. He wasn’t happy about it ending the way it did. “Ted Mack didn’t buy Peoples,” Tuff said. “Pabst did.” You can understand his disappointment, but there is no truth to that statement.

After he lost his job at Peoples, Tuff worked for a couple of years as a woodworker at Quality Builders. After he retired, he did a lot of fishing on the Fox River. He used hand-tied streamer flies and had a regular spot he liked that was near his home on School Avenue.

George “Tuff” Boeder passed away in that home on June 16, 1983. He was 69 years old.

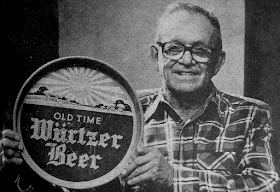

|

| George "Tuff" Boeder. |

Tuff Boeder was born in Oshkosh on January 15, 1914. He was second-generation American. His grandfather Friedrich Böder had come to the U.S. in 1880 from Pommern, which was then a province of Germany. Tuff lived all his life in Oshkosh. He grew up in a modest home on the east side of town, at what is now 1003 School Avenue. His boyhood home still stands.

|

| 1003 School Avenue. Oshkosh, Wisconsin. |

His father, Paul Boeder, was already working in the beer business when Tuff was born. Paul had started as a bookkeeper at the Schlitz distribution house on Division Street in Oshkosh in 1911. At that time, Schlitz was trying to claw its way back to prominence in the Oshkosh market. The brewery had struggled here for much of the previous decade thanks, in large part, to the rising fortunes of the Oshkosh Brewing Company.

|

| Oshkosh Daily Northwestern; November 29, 1912 |

That campaign had little success here. Schlitz finally gave up on Oshkosh and closed its branch here in 1918. Paul Boeder found a new job on the southside keeping the books for Peoples Brewing. He was there when Prohibition hit in 1920. The brewery quit making beer and started selling soda, fruit juice, near beer, malt tonics…

Prohibition ended in 1933. Peoples Brewing immediately went back to making real beer. Paul Boeder got Tuff a job there in 1936. Tuff married Ruth Pratsch that same year. He was 22 then. He’d come of age during the Great Depression when work in Oshkosh was hard to find. This was his first real job. He started out at Peoples putting labels on bottles.

“A lot was done by hand back then,” Tuff said. “We had to label each bottle separately. If we did 30 barrels a day that was a lot.”

Tuff moved up the ranks. In the early 1940s he began working as a route driver delivering Würtzer Beer and Old Derby Ale to local taverns and beer depots. He made $34 a week. Most of his stops were in and around town. Peoples had little need for wider distribution. The brewery was already growing at a good clip. Between 1943 and 1953 sales increased by 200 percent. “The taverns in Oshkosh wouldn’t buy that Milwaukee beer as long as Oshkosh had its own breweries,” Tuff said.

About 1951, Tuff moved back into the brewery. He went to work in the bottling department. Now he was making almost $55 for a 40-hour week. The days of hand labeling bottles were over. It had been automated. On a good day, that line could put out 50,000 bottles of beer.

In 1953, Tuff moved over to the brewhouse and began working as a brewer. He and Wilhelm Kohlhoff became the two principal brewers at Peoples. Kohlhoff had just started at the brewery. He was from Pommern, Germany; like Tuff’s family. The two of them became fast friends.

|

| Wilhelm Kohlhoff |

The brewmaster then was Dale Schoenrock. He had been with Peoples since 1940. Schoenrock was all business when it came to making beer.

"I’d get to work at three in the morning and start heating up the mash tub," Tuff said. "The temperature was critical. If the brewmaster said 56.5 degrees Celsius, he didn’t mean 56 or 57."

|

| Dale Schoenrock |

In 1956, Tuff was named Assistant Brewmaster. The work wasn't much different, but the pay was better. By 1957, he was making $73.40 a week. Tuff and Kohlhoff worked in shifts, turning out two or three batches of beer a day. The brewery was producing over 30,000 barrels of lager beer a year at this point.

"We used gravity to move the beer," Tuff said. "There were four floors. When it hit bottom it was done." At least Tuff's part was done. From there it went to the beer cellars for fermentation. "The brew would ferment for eight or nine days," he said. "It’s really going strong on day two. As it ferments, it gives off carbon dioxide gas and we’d collect and store this gas in huge tanks. Later on, this gas goes back into the beer (to carbonate it)."

Peoples had its own powerhouse and Tuff always worried that the massive steam generator would give out while he was brewing. It happened more than once. He had to "baby" those batches to completion. "If you lost your steam you could lose a brew," Tuff said. “That’s $5,000 down the drain. I never ruined a brew as long as I worked there."

Tuff told an incredible story that I can't verify. He said there was a period (presumably in the 1950s) when the Stroh Brewery of Detroit was making beer at Peoples. "They were having all kinds of trouble with their equipment, so we brewed it for them," Tuff said. "There were semis here, one right after the other picking up the beer. They gave us a recipe so we could match the flavor, but it wasn’t THE recipe. That’s always a secret."

There has to be more to this. When Tuff was brewing at Peoples, the Stroh Brewery was selling far more beer than Peoples was capable of making. By 1957 Stroh's annual output was 2.7 million barrels. The capacity of the Peoples brewery was well under 100,000 barrels annually. That said, the Stroh Brewery was shut down for 45-days by a strike in 1958. Perhaps Tuff’s recollections are in some way connected to that event. That’s just speculation, though.

Tuff worked in the brewhouse until the very end, 1972, when Peoples went bankrupt and closed. Theodore Mack was running Peoples then. Mack had come from Milwaukee where he had worked at Pabst. Tuff said that Mack offered to help him get a job at Pabst after Peoples shut down. Tuff didn’t want it. He didn’t want to move to Milwaukee. “I was getting too old,” he said. “Too close to retirement.”

Tuff had 36 years in at Peoples when the brewery failed. He wasn’t happy about it ending the way it did. “Ted Mack didn’t buy Peoples,” Tuff said. “Pabst did.” You can understand his disappointment, but there is no truth to that statement.

After he lost his job at Peoples, Tuff worked for a couple of years as a woodworker at Quality Builders. After he retired, he did a lot of fishing on the Fox River. He used hand-tied streamer flies and had a regular spot he liked that was near his home on School Avenue.

George “Tuff” Boeder passed away in that home on June 16, 1983. He was 69 years old.

––––––––––––––––––

A note on the quotes: They were sourced from an article published in the April 17,1980 Advance-Titan; the UW-Oshkosh student newspaper. The piece, ostensibly about Oshkosh brewing history, is riddled with factual errors. The article’s value is derived from the quotations it contains of former Oshkosh brewery workers. My aim here was to frame the Boeder quotes within a more fitting context. Thursday, July 25, 2019

Hidden Valley Hops Farm

Justin Gloede is doing something in the Town of Winchester that hasn't been done there in almost 140 years. He's putting in a new hopyard.

Three years ago, Gloede planted a small set of hops on his family's farm in the Town of Winchester. Those plants have thrived. The bounty of hop cones they produced surprised and encouraged him. This year, Gloede decided to get serious about hops. He built a 12-pole trellis that covers about a tenth of an acre and began putting down roots.

"I have about 70 plants in the ground right now," Gloede says. "I’ll have roughly 110 plants total after I finish planting next year. I’m also going organic. No pesticides."

This is a long-term project. The typical hop yard takes 4-5 years to reach its potential in terms of yield. Gloede's work now is mainly about getting his plants established and setting a foundation for future growth. Mother Nature hasn’t been much help.

"What a year to try and grow hops," Gloede says. "All this rain is killing me."

Nevertheless, Gloede's yard is taking root. He's put in a diverse mix that includes Cascade, Chinook, Hallertau, Nugget, Saaz, and Tettnanger. He’s also planted a hop that goes back to the origins of hop growing in Winnebago County.

Gloede was given permission to harvest roots from the site of the old Silas Allen farm in Allenville. Allen's hopyard, planted sometime around 1849, was likely the first in Winnebago County. Hops still grow wild there. That plot is located about a mile from Gloede's yard and the hops he's transplanted from it have quickly acclimated to their new home.

"The Allenville hops are exploding," he says. "I’m already looking at putting in two more rows of it, but that's still to be determined."

Gloede has joined the Wisconsin Hop Exchange, a statewide cooperative established to assist hop growers, and he would eventually like to help supply area breweries and homebrewers with locally sourced hops. He has room to expand and plans to purchase a pelletizer once he's able to produce a sufficient harvest.

"I’m going to find a way to get a pelletizer at some point," Gloede says. And I’ll be open to pelletizing other peoples hops, too. No idea if there’s a market for that, but we'll see."

Gloede is joining a farming lineage that was nearly forgotten in Winnebago County. In the 1870s there were more than 115 acres of hops spread across the four northcentral Winnebago County townships of Clayton, Vinland, Winchester, and Winneconne. By the early 1880s, all of it had been plowed under. Gloede's yard is in the heart of those fertile lands. He could not have picked a better place to stage a revival.

You can follow the progress of Gloede's yard at the Hidden Valley Hops Farm Facebook page.

|

| Justin Gloede (green shirt) in his hop yard. |

Three years ago, Gloede planted a small set of hops on his family's farm in the Town of Winchester. Those plants have thrived. The bounty of hop cones they produced surprised and encouraged him. This year, Gloede decided to get serious about hops. He built a 12-pole trellis that covers about a tenth of an acre and began putting down roots.

"I have about 70 plants in the ground right now," Gloede says. "I’ll have roughly 110 plants total after I finish planting next year. I’m also going organic. No pesticides."

This is a long-term project. The typical hop yard takes 4-5 years to reach its potential in terms of yield. Gloede's work now is mainly about getting his plants established and setting a foundation for future growth. Mother Nature hasn’t been much help.

"What a year to try and grow hops," Gloede says. "All this rain is killing me."

|

| Another rain-soaked day in the Town of Winchester. |

Nevertheless, Gloede's yard is taking root. He's put in a diverse mix that includes Cascade, Chinook, Hallertau, Nugget, Saaz, and Tettnanger. He’s also planted a hop that goes back to the origins of hop growing in Winnebago County.

Gloede was given permission to harvest roots from the site of the old Silas Allen farm in Allenville. Allen's hopyard, planted sometime around 1849, was likely the first in Winnebago County. Hops still grow wild there. That plot is located about a mile from Gloede's yard and the hops he's transplanted from it have quickly acclimated to their new home.

"The Allenville hops are exploding," he says. "I’m already looking at putting in two more rows of it, but that's still to be determined."

Gloede has joined the Wisconsin Hop Exchange, a statewide cooperative established to assist hop growers, and he would eventually like to help supply area breweries and homebrewers with locally sourced hops. He has room to expand and plans to purchase a pelletizer once he's able to produce a sufficient harvest.

"I’m going to find a way to get a pelletizer at some point," Gloede says. And I’ll be open to pelletizing other peoples hops, too. No idea if there’s a market for that, but we'll see."

Gloede is joining a farming lineage that was nearly forgotten in Winnebago County. In the 1870s there were more than 115 acres of hops spread across the four northcentral Winnebago County townships of Clayton, Vinland, Winchester, and Winneconne. By the early 1880s, all of it had been plowed under. Gloede's yard is in the heart of those fertile lands. He could not have picked a better place to stage a revival.

You can follow the progress of Gloede's yard at the Hidden Valley Hops Farm Facebook page.

Monday, July 22, 2019

Another "First" for Chief Oshkosh

On this day in 1963, the Oshkosh Brewing Company introduced 8-packs of what it was calling the glass can, a 12-ounce stubby bottle of beer. OBC claimed it was the first Wisconsin brewery to offer this style of non-returnable bottle beer in 8-packs. Everybody else had 6-packs. The 8-packs sold for about $1.25. A case of returnable bottles of Chief Oshkosh went for $2.49 at that time.

|

| These bottles are circa 1967. |

|

| A 1968 display. |

|

| Oshkosh Daily Northwestern, July 20, 1963. |

Thursday, July 11, 2019

Craig Zoltowski in The Cellar

Over the past month, The Cellar, a beer and winemaking supply shop in Oshkosh, has been undergoing an expansion. Behind that expansion is one of the shop’s new owners. His name is Craig Zoltowski.

The Cellar opened in Fond du Lac in 2009 and moved to Oshkosh in 2016. Zoltowski and co-owner Jeff Duhacek purchased the business at 465 N. Washburn St. from Dave Koepke this past May. They've been operating the store since the beginning of June.

It's the first time either Zoltowski or Duhacek have run a homebrew shop, but they come to the business with bona fides, especially on the science side of brewing. Duhacek is a Ph.D. chemist. Zoltowski has a master’s degree in chemical engineering and an MBA. He's also a professional brewer.

Zoltowski is co-owner of Emprize Brew Mill, a brewpub that opened a year ago in Menasha. And with that, his path changed. "I've been in corporate America pretty much my entire career,” Zoltowski says. "I decided to get out and do this, do something I'm really passionate about."

His enthusiasm shows when he talks about his plans for the store. "We want to optimize this place," Zoltowski says. "We’re really trying to add a huge capability here that will help the homebrewers and small breweries and winemakers in this area. We’re adding more of just about everything.”

"We've added a lot of equipment," Zoltowski says. "We tripled out Blichmann inventory. We've added CO2 and nitrogen tanks. We have more corny kegs and fermenters and now we have sanke kegs and keg washers. We've also added more kits for wine and beer, and we've added a lot more honey for people who make mead. We're carrying a wider variety of yeast and hops. We're also starting to bring in more locally grown hops from Wisconsin and Michigan. We’ve probably added five times the amount of grain and new varieties of it. We also have a new, three-roller malt mill coming that we can really dial in, so we can offer different grain crushes for people who want that."

Zoltowski says his top priority now is a web-based ordering system. If it works as planned it will make the shop's inventory accessible online and allow people to place orders for pickup.

"We want to arrange it so we have people’s orders ready when they come in," he says. "What I'm thinking is, if you get an order in by 5 p.m. I can have it ready for pick-up by 10 a.m. the next morning. We're about to start beta-testing that and I'm hoping that in a month or so it will be ready. We want to make shopping here more convenient."

As part of that effort, the store is now open on Sundays. "That way if you are brewing on the weekend and run out of something you can come in and still finish your batch," Zoltowski says. "We're just trying to find ways to differentiate ourselves and provide a service. And we have the experience where we can answer questions and help people through their issues."

The educational component is something Zoltowski is also looking to expand. "Tim Pfeister is going to continue teaching classes here," he says. "Our goal is to eventually do a class every month. We’d like to be able to build it into something like a curriculum.”

Zoltowski says it's the community aspect of the shop that has been the most rewarding part of it for him so far.

"I enjoy the customer side of it,” Zoltowski says. "It's been fun. I'm an engineer, I like problem-solving and I really like teaching people. We’re trying to connect to the brewing community, both homebrewing as well as the nano and microbrewers and make it more like a co-op effort. We want to be a part of that community. There’s something powerful about that.”

|

| Craig Zoltowski at work in The Cellar |

The Cellar opened in Fond du Lac in 2009 and moved to Oshkosh in 2016. Zoltowski and co-owner Jeff Duhacek purchased the business at 465 N. Washburn St. from Dave Koepke this past May. They've been operating the store since the beginning of June.

It's the first time either Zoltowski or Duhacek have run a homebrew shop, but they come to the business with bona fides, especially on the science side of brewing. Duhacek is a Ph.D. chemist. Zoltowski has a master’s degree in chemical engineering and an MBA. He's also a professional brewer.

Zoltowski is co-owner of Emprize Brew Mill, a brewpub that opened a year ago in Menasha. And with that, his path changed. "I've been in corporate America pretty much my entire career,” Zoltowski says. "I decided to get out and do this, do something I'm really passionate about."

His enthusiasm shows when he talks about his plans for the store. "We want to optimize this place," Zoltowski says. "We’re really trying to add a huge capability here that will help the homebrewers and small breweries and winemakers in this area. We’re adding more of just about everything.”

|

| Inside The Cellar. |

"We've added a lot of equipment," Zoltowski says. "We tripled out Blichmann inventory. We've added CO2 and nitrogen tanks. We have more corny kegs and fermenters and now we have sanke kegs and keg washers. We've also added more kits for wine and beer, and we've added a lot more honey for people who make mead. We're carrying a wider variety of yeast and hops. We're also starting to bring in more locally grown hops from Wisconsin and Michigan. We’ve probably added five times the amount of grain and new varieties of it. We also have a new, three-roller malt mill coming that we can really dial in, so we can offer different grain crushes for people who want that."

Zoltowski says his top priority now is a web-based ordering system. If it works as planned it will make the shop's inventory accessible online and allow people to place orders for pickup.

"We want to arrange it so we have people’s orders ready when they come in," he says. "What I'm thinking is, if you get an order in by 5 p.m. I can have it ready for pick-up by 10 a.m. the next morning. We're about to start beta-testing that and I'm hoping that in a month or so it will be ready. We want to make shopping here more convenient."

As part of that effort, the store is now open on Sundays. "That way if you are brewing on the weekend and run out of something you can come in and still finish your batch," Zoltowski says. "We're just trying to find ways to differentiate ourselves and provide a service. And we have the experience where we can answer questions and help people through their issues."

The educational component is something Zoltowski is also looking to expand. "Tim Pfeister is going to continue teaching classes here," he says. "Our goal is to eventually do a class every month. We’d like to be able to build it into something like a curriculum.”

Zoltowski says it's the community aspect of the shop that has been the most rewarding part of it for him so far.

"I enjoy the customer side of it,” Zoltowski says. "It's been fun. I'm an engineer, I like problem-solving and I really like teaching people. We’re trying to connect to the brewing community, both homebrewing as well as the nano and microbrewers and make it more like a co-op effort. We want to be a part of that community. There’s something powerful about that.”

Tuesday, July 9, 2019

Peoples Beer at the Oshkosh Public Library

Wednesday, July 17, I’ll be talking Oshkosh beer history at the Oshkosh Public Library. The talk will focus on Peoples Brewing Company of Oshkosh and the incredible story of Wilhelm Kohlhoff, the last of the German-born brewers to make beer there.

It won’t be all talk. We’ll also have a keg of beer made by Jody Cleveland, head brewer at Bare Bones Brewery. Jody made this beer from the original recipe supplied by Kohlhoff. This is as close as you’re ever likely to get to the Peoples Beer that flowed in Oshkosh during the 1950s and 1960s.

The talk begins at 6 p.m. and will take place under the dome in the library. Free samples of beer will be available immediately following the talk. Hope to see you there!

|

| Wilhelm Kohlhoff |

It won’t be all talk. We’ll also have a keg of beer made by Jody Cleveland, head brewer at Bare Bones Brewery. Jody made this beer from the original recipe supplied by Kohlhoff. This is as close as you’re ever likely to get to the Peoples Beer that flowed in Oshkosh during the 1950s and 1960s.

The talk begins at 6 p.m. and will take place under the dome in the library. Free samples of beer will be available immediately following the talk. Hope to see you there!

Monday, July 1, 2019

Lost on Wisconsin

Here's an extinct Wisconsin Street bar I'm sure a lot of Oshkoshers will remember. Over the years, it’s gone by many different names: The Fox River Bar, The Lost Dutchman, Nantuckets, The Bubbler, The Buffalo Breath Saloon, Nad’s... In 1934, it was John Mailahn's Fox River Bar and it looked like this...

That picture has plenty to say. It starts with the men we see gathered around a table-top radio. They were a crew of workers from the Radford Company. Radford was just across Hancock Street from Mailahn's tavern. Maybe these guys were on their lunch break. Hitting the bar for a couple of beers at midday was once common among Oshkosh mill workers.

You might have noticed the cropped "BEER" sign hanging on the corner of the tavern near the entrance. Here's what it would have looked like in full and in color.

That sign was made for the Oshkosh Brewing Company by the Veribrite Sign Company of Chicago. It's a pre-Prohibition piece, circa 1917. Somehow it survived the dry years of 1920 to 1933. Many of those signs were consigned to the trash heap when Prohibition hit.

Behind the men is another sign painted on the side of the tavern. It's for Chief Oshkosh Special Old Lager. That sign would have gone up shortly after Prohibition was repealed. Chief Oshkosh Special was introduced by the Oshkosh Brewing Company during Prohibition as a non-alcoholic brew. When the dry law ended, they made it into a real beer in and re-branded it as Chief Oshkosh Special Old Lager.

It's no accident that the place was draped with Oshkosh Brewing Company advertising. The bar was owned by the brewery. Before we get into that, let's draw a bead on exactly where the tavern stood. Below is a map from 1949. The Fox River Bar is shown at 44 Wisconsin Street with a red star in front of it.

All of that is gone. Here's a recent aerial view of that same area. The building with the red and white roof is Mahoney's Restaurant & Bar. The red star is approximately where the Fox River River Bar stood.

There had been a tavern at that site since 1894 when a mill worker named Fred Martin converted his home there into a saloon and grocery store. The groceries didn't last. The saloon did.

Herman Mailahn became the saloon's proprietor in 1903. He had been born in 1875 and had spent nearly all his life in Oshkosh. He left for a few months in 1898 to go to the Philippines where he fought in the Spanish-American War. After he returned home, he took a bartending job at a saloon on High Ave. that no longer stands. A couple of years after that, he became the keeper of the bar at 44 Wisconsin Street. But that was short lived. And so was Herman Mailahn. He died in 1905 at the age of 29 from an obstruction of the bowels.

In swooped the Oshkosh Brewing Company. At that time, OBC was buying up saloon properties in Oshkosh in a bid to take control of the Oshkosh beer market. The saloon at 44 Wisconsin became part of that gambit. Just two months after Herman Mailahn died, the brewery bought the tavern and installed Herman's younger brother John as its proprietor. John Mailahn would run that saloon for the next 47 years. The Oshkosh Brewing Company was his landlord for all of that time.

Prior to 1920, Mailahn's saloon was a straight-up tied house. The only beer served there was beer made by the Oshkosh Brewing Company. That ended when Prohibition hit and the brewery had to stop making beer. Nonetheless, Mailahn managed to keep the bar open. He ran it as a soft drink parlor and lunch counter. Legitimately. Mailahn was never busted on a dry-law violation.

When Prohibition ended in 1933, the beer returned but the old tied-house arrangements had been made illegal. Some breweries, however, gamed the system. The Oshkosh Brewing Company did. OBC transferred its saloon properties to a real-estate holding company whose directors were the same men who ran the brewery. They continued to have influence over the tavern keepers who leased property from them. In some of these places, you'd still find nothing but the landlord's beer on tap. Beer from other breweries was made available, but only in bottles – a more expensive option.

By the time John Mailahn retired in 1952, the bar at 44 Wisconsin had been known as the Fox River Bar for nearly 20 years. And it would retain that name for the next 20 years. For most of that time, it was run by a fellow named Clarence Fischer.

Fischer was an eighth-grade dropout born in Marshfield in 1907. He had been driving a coal truck before finding his true calling in 1953 when he took over the Fox River Bar. Fischer appears to have done quite well there. He purchased the building in 1965. Its address had been changed by then to 100 Wisconsin Street following the 1957 ordinance that revamped Oshkosh's street numbering system.

Fischer ran a welcoming, working-class tavern. Oshkosh author Randy Domer remembers it fondly. In his book Oshkosh: Land of Lakeflies, Bubblers and Squeaky Cheese, Domer recalls, "One of my favorite memories was listening to the tunes coming out of the old Seeburg jukebox at the Fox River Bar on Wisconsin Ave. It was where my dad liked to stop for a couple of beers on occasion and sometimes he would let me tag along."

Domer liked the place so much that he managed to save one of the old card tables that had been used there. In the photo below you can see the side pocket where a player could stow their beer while the cards skimmed across the table.

Clarence Fischer retired from the Fox River Bar in 1970. Things were changing. With the growth of the university, "the strip" of bars along Wisconsin Street went from being working class places to hangouts for younger people and college kids. For 80 years those bars had served the folks who worked in the mills and factories clustered around Wisconsin Street. That time was coming to an end.

The next photo is from 1973. The old Fox River Bar was painted red at this point and called My Brother's Place, a name borrowed from a recently closed tavern that had been on High and Osceola streets.

Through the 70s, 80s, and 90s the name of the tavern and its owners seemed to change every few years. In the late 1980s it was the Buffalo Breath Saloon. It was managed by Jeff Fulbright, who would go on, in 1991, to launch the Mid-Coast Brewing Company of Oshkosh and Chief Oshkosh Red Lager. Here's a look inside the Buffalo Breath Saloon...

In the end, the tavern was known as Nad's. It was run then by Nate Stiefvater, who now operates Barley & Hops Pub and Beer Garden on North Main Street. Nad's closed in 2001. The building, which was then almost 120 years old, was demolished soon after. Here's how it appeared in its final years...

Look around the next time you’re on Wisconsin Street near the bridge. That stretch used to be full of industry and saloons. All that has been cleared out. There’s not a hint left of how it once was.

|

| Photo courtesy of Janet Wissink. |

That picture has plenty to say. It starts with the men we see gathered around a table-top radio. They were a crew of workers from the Radford Company. Radford was just across Hancock Street from Mailahn's tavern. Maybe these guys were on their lunch break. Hitting the bar for a couple of beers at midday was once common among Oshkosh mill workers.

You might have noticed the cropped "BEER" sign hanging on the corner of the tavern near the entrance. Here's what it would have looked like in full and in color.

That sign was made for the Oshkosh Brewing Company by the Veribrite Sign Company of Chicago. It's a pre-Prohibition piece, circa 1917. Somehow it survived the dry years of 1920 to 1933. Many of those signs were consigned to the trash heap when Prohibition hit.

Behind the men is another sign painted on the side of the tavern. It's for Chief Oshkosh Special Old Lager. That sign would have gone up shortly after Prohibition was repealed. Chief Oshkosh Special was introduced by the Oshkosh Brewing Company during Prohibition as a non-alcoholic brew. When the dry law ended, they made it into a real beer in and re-branded it as Chief Oshkosh Special Old Lager.

It's no accident that the place was draped with Oshkosh Brewing Company advertising. The bar was owned by the brewery. Before we get into that, let's draw a bead on exactly where the tavern stood. Below is a map from 1949. The Fox River Bar is shown at 44 Wisconsin Street with a red star in front of it.

All of that is gone. Here's a recent aerial view of that same area. The building with the red and white roof is Mahoney's Restaurant & Bar. The red star is approximately where the Fox River River Bar stood.

There had been a tavern at that site since 1894 when a mill worker named Fred Martin converted his home there into a saloon and grocery store. The groceries didn't last. The saloon did.

Herman Mailahn became the saloon's proprietor in 1903. He had been born in 1875 and had spent nearly all his life in Oshkosh. He left for a few months in 1898 to go to the Philippines where he fought in the Spanish-American War. After he returned home, he took a bartending job at a saloon on High Ave. that no longer stands. A couple of years after that, he became the keeper of the bar at 44 Wisconsin Street. But that was short lived. And so was Herman Mailahn. He died in 1905 at the age of 29 from an obstruction of the bowels.

In swooped the Oshkosh Brewing Company. At that time, OBC was buying up saloon properties in Oshkosh in a bid to take control of the Oshkosh beer market. The saloon at 44 Wisconsin became part of that gambit. Just two months after Herman Mailahn died, the brewery bought the tavern and installed Herman's younger brother John as its proprietor. John Mailahn would run that saloon for the next 47 years. The Oshkosh Brewing Company was his landlord for all of that time.

Prior to 1920, Mailahn's saloon was a straight-up tied house. The only beer served there was beer made by the Oshkosh Brewing Company. That ended when Prohibition hit and the brewery had to stop making beer. Nonetheless, Mailahn managed to keep the bar open. He ran it as a soft drink parlor and lunch counter. Legitimately. Mailahn was never busted on a dry-law violation.

| From the 1926 Oshkosh City Directory. |

When Prohibition ended in 1933, the beer returned but the old tied-house arrangements had been made illegal. Some breweries, however, gamed the system. The Oshkosh Brewing Company did. OBC transferred its saloon properties to a real-estate holding company whose directors were the same men who ran the brewery. They continued to have influence over the tavern keepers who leased property from them. In some of these places, you'd still find nothing but the landlord's beer on tap. Beer from other breweries was made available, but only in bottles – a more expensive option.

By the time John Mailahn retired in 1952, the bar at 44 Wisconsin had been known as the Fox River Bar for nearly 20 years. And it would retain that name for the next 20 years. For most of that time, it was run by a fellow named Clarence Fischer.

Fischer was an eighth-grade dropout born in Marshfield in 1907. He had been driving a coal truck before finding his true calling in 1953 when he took over the Fox River Bar. Fischer appears to have done quite well there. He purchased the building in 1965. Its address had been changed by then to 100 Wisconsin Street following the 1957 ordinance that revamped Oshkosh's street numbering system.

|

| A bar token with the new address of the Fox River Bar. |

Fischer ran a welcoming, working-class tavern. Oshkosh author Randy Domer remembers it fondly. In his book Oshkosh: Land of Lakeflies, Bubblers and Squeaky Cheese, Domer recalls, "One of my favorite memories was listening to the tunes coming out of the old Seeburg jukebox at the Fox River Bar on Wisconsin Ave. It was where my dad liked to stop for a couple of beers on occasion and sometimes he would let me tag along."

Domer liked the place so much that he managed to save one of the old card tables that had been used there. In the photo below you can see the side pocket where a player could stow their beer while the cards skimmed across the table.

Clarence Fischer retired from the Fox River Bar in 1970. Things were changing. With the growth of the university, "the strip" of bars along Wisconsin Street went from being working class places to hangouts for younger people and college kids. For 80 years those bars had served the folks who worked in the mills and factories clustered around Wisconsin Street. That time was coming to an end.

The next photo is from 1973. The old Fox River Bar was painted red at this point and called My Brother's Place, a name borrowed from a recently closed tavern that had been on High and Osceola streets.

|

| Photo courtesy of Dan Radig |

Through the 70s, 80s, and 90s the name of the tavern and its owners seemed to change every few years. In the late 1980s it was the Buffalo Breath Saloon. It was managed by Jeff Fulbright, who would go on, in 1991, to launch the Mid-Coast Brewing Company of Oshkosh and Chief Oshkosh Red Lager. Here's a look inside the Buffalo Breath Saloon...

|

| Photo courtesy of Jeff Fulbright. |

In the end, the tavern was known as Nad's. It was run then by Nate Stiefvater, who now operates Barley & Hops Pub and Beer Garden on North Main Street. Nad's closed in 2001. The building, which was then almost 120 years old, was demolished soon after. Here's how it appeared in its final years...

Look around the next time you’re on Wisconsin Street near the bridge. That stretch used to be full of industry and saloons. All that has been cleared out. There’s not a hint left of how it once was.