|

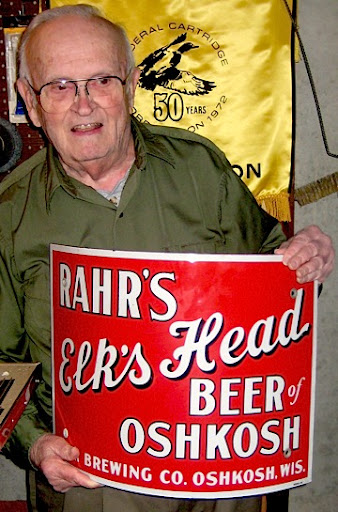

| Charles Rahr III |

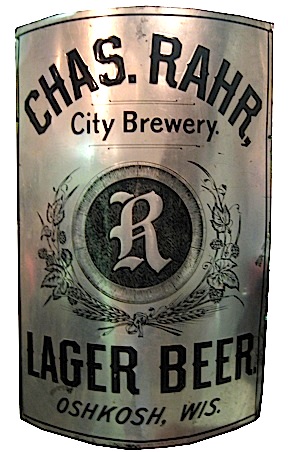

Rahr’s brewing heritage recalls an age that seems especially distant now. His great-grandfather, Charles Rahr, was born in the Rhine Province of Prussia in 1836, years before the first Pilsner beer had been brewed or the discovery that yeast was responsible for fermentation had been made. After learning to brew, the elder Rahr emigrated to America in 1855 and in 1865 established The City Brewery in Oshkosh at what is now 1362 Rahr Ave. He operated the brewery until 1884 and was instrumental in the training of both his son, Charles Jr., and grandson, Carl. In 1917 Carl Rahr assumed control of brewing operations at the Rahr Brewery and in 1928 fathered a son he named Charles Rahr III.

For the young Charles Rahr III, brewing beer was part of everyday life. “I grew up across the street from the brewery,” Rahr recalls, “and from a very young age I helped out around the brewery. Even as a little kid I used to watch my dad brew the beer. It was our life.”

By the time he reached adulthood, Rahr was already well acquainted with the life of a practical brewer and after graduating from high-school, he balanced what he’d learned in the brewery with a more formal education in the business side of the operation. He attended the Oshkosh State College and later the Oshkosh Business College before taking brewing courses at the Seibel Institute in Chicago. By 1952 Rahr was back in Oshkosh and back at the brewery.

As the new brewmaster of the Rahr Brewing Company, Rahr picked up where his father had left off, brewing a distinctive beer that had a dedicated following in the Oshkosh area. In comparison to other lagers of the period, Rahr’s Elk’s Head Beer was something different. According to Rahr, the beer had changed little over the years and was essentially the same as that which the Rahr family had brewed prior to Prohibition. The composition of the beer confirms this. Four separate grains were used in the production of Elk’s Head Beer resulting in a lager that would have had less in common with its single-malt contemporaries than it would have with many of today’s craft beers.

At a time when most American breweries were doing all they could to make their product ever more bland and indistinguishable, Rahr’s Elk’s Head Beer harkened back to an earlier period. At the same time, Rahr Brewing was a precursor of things to come. Today we would recognize it as an artisanal brewery, making quality beer in small batches for a local audience. It was a neighborhood brewery surrounded by homes where much of the process was hands-on and Rahr remembers well the effort that went into brewing each batch. “We had a beautiful set-up for our brewhouse,” he says, “but making the beer took a lot of hard work.”

The process would typically begin a day before the actual brew day when Rahr would prepare the water for brewing and begin grinding the malt. The specially designed malt mill Rahr used came from the Gettleman Brewery of Milwaukee and was configured to tear apart the husk of the grain instead of crushing it, as was typically done. Rahr stresses that these seemingly small differences were important to the final product. “All of the brewers had access to the same or very similar ingredients,” he says. “What set you apart were the techniques you used to make the beer.”

Rahr usually brewed beer two or three days a week with brew days often beginning as early as 2:00 a.m. “It was a long day,” Rahr says and much of it was dedicated to an elaborate step mashing process that took place in a mash tun that could produce just over 100 barrels of wort. According to Rahr, “A large mash could take as long as five hours to complete.” Separating the wort from the grain and clearing it would often add another couple of hours as Rahr was a stickler for producing a clean wort. “That was an important part of it,” he says. “The wort had to be clear before it went into the brew kettle.”

After transfer into a steam-heated kettle acquired from Blatz Brewing, the wort would be brought to a boil. Rahr would then add the first of the beer’s three hop additions. Rahr Brewing used American grown hops from the Yakima Valley of Washington that would arrive at the brewery in bails. “We’d get bails and bails of those hops,” Rahr says, “and they had to be added to the kettle by hand. That part of it was strenuous.” After boiling for more than an hour, the wort was strained to remove the hops and passed over a chiller where it would cool to about 50º before being transferred to a fermentation vessel.

In the latter years of the Rahr brewery, the yeast used to ferment the beer was also supplied by Gettleman Brewery. “We’d go down to Milwaukee to get the yeast and bring it back in big, insulated milk cans to ensure that it stayed fresh,” Rahr says.

A typical fermentation would last about a week and when fermentation was complete the beer would be taken off the yeast and stored in a lagering tank in the cellar of the brewery where it would be held at a low temperature. Here the beer was given time to clarify, age and mellow before being carbonated with CO2 and packaged. If all went well, the beer could be ready for sale in about a month.

But it didn’t always go well. Rahr remembers a time when he missed one of the temperature raises while he was conducting the mash. The result would have been virtually unnoticeable to the average drinker. “We were very particular about our beer, though,” Rahr says. “I couldn’t let it go like that. We went back and blended that beer with another to be certain that the quality of the beer wouldn’t suffer.”

By the middle of the 1950s, though, quality beer was becoming a thing of the past. The age of industrial lager was here. Small Wisconsin breweries producing flavorful beer were forced to the margins by brewing corporations with inflated advertising budgets. Beer became less about flavor and more about image as the homogenization of taste was conflated with modernity and progress. The demand for quality beer rapidly shrank. Rahr Brewing faced the same bleak fate that beset countless other small brewers. From 1954 to 1955 sales at Rahr Brewing fell by 35%. When the brewery closed in 1956 Rahr was on course to produce less than 3,000 barrels for the year. The end of an era had arrived.

After the brewery closed, Charles Rahr III left brewing behind and eventually settled into a career as the director of Highland Memorial Park in Appleton where he worked for more than 20 years until his retirement. A half century later, though, he still often thinks about his family’s brewery. “You can’t help but think about it when you were there that many years,” he says. And the brewmaster in him still takes pride in his beer. “We were happy with our beer. We had a very good product. There was no horsing around. We purchased good ingredients and we knew how to use them!”

Always entertaining to read you blog Lee, thanks

ReplyDeleteThanks, Randy. Getting to meet Chuck Rahr was incredible.

ReplyDeleteHi Lee: I would be interested in using a version of this story in the Breweriana Collector magazine. We could also promote your book. Would you mind contacting e at ken@consumertruth.com? Thanks very much!

ReplyDelete