|

| Jeff Fulbright at the Stevens Point Brewery |

“Did you know one of America’s great little beers comes from Oshkosh?” That was the lead-in to a magazine advertisement from 1993 for Chief Oshkosh Red Lager. Seventeen years later the beer and the company that produced it are gone, but the man who almost single-handedly returned the name Oshkosh to beer shelves throughout the Midwest is still here and his innovations continue to influence American craft brewing. Jeff Fulbright’s beer was the first American beer to identify itself as a Red Lager, it was the first Craft Beer to be sold in cans and it was the first American beer to use Belgian Cara-Munich malt. Now, almost 20 years after Fulbright began making his beer, Red Lagers are ubiquitous, craft brewers are waking-up to the advantages of canning their beer and nearly every brew-pub and craft brewery in America makes at least some of their beer using the Belgian Malts that Fulbright helped to introduce.

Chief Oshkosh Red Lager was produced for just four years, but its roots run much deeper. As a college student at the University of Wisconsin - Oshkosh in the 1970s, Jeff Fulbright knew about the demise of Chief Oshkosh beer and had a vague notion about reviving the brand. The idea grew more substantial in the mid-80s while Fulbright was working as a restaurateur in Florida. “I saw this thing coming up,” Fulbright said. “I was a drinker of European beer and when the American micro-beer movement started I was immediately attracted to the idea of creating my own beer and selling it to the public.”

Fulbright moved back to Wisconsin and began putting together a business plan for a new brewery based in Oshkosh. As part of his research, he attended the Great American Beer Festival where he had a fortuitous encounter with Jim Koch, founder of the Boston Beer Company and brewer of Samuel Adams beer. Fulbright told Koch of his desire to open a brewery and sell an updated version of Chief Oshkosh beer. Koch’s response set the course for what would become the Mid-Coast Brewing Company of Oshkosh. Koch advised Fulbright to forget about building his own brewery. The market already had too much capacity. He told Fulbright he’d have a better shot if he made his beer at someone else's brewery. Koch also suggested that Fulbright go back to school and learn first-hand what it takes to make great beer. Fulbright took the advice to heart. He enrolled at the Siebel Institute and began his training as a brewer.

When he arrived at Siebel, Fulbright had a solid idea of the beer he wanted to make. “My favorite style of beer at the time was Oktoberfest,” Fulbright says. “I wanted to do a toned-down version of an Oktoberfest that people could drink throughout the year.” Fulbright also wanted his own stamp on the beer. He began experimenting with specialty malts from Belgium. These malts were largely unknown to American brewers at the time, but the Siebel Institute had recently begun importing them for testing. Eventually Fulbright settled on a Belgian Cara-Munich malt that gave the beer its sweet, malty character and distinctive “red” hue. Fulbright says he’d love to claim all the credit for developing the beer, but admits that he was still learning about brewing as he worked-up the recipe. Much of what he learned came from David S. Ryder, who went on to become the Brewmaster for Miller Brewing, but was then an instructor at Siebel. “Ryder was a brilliant brewer,” Fulbright says, “and he had a good idea of what I wanted to brew.” With the help of Ryder, Fulbright honed the recipe by brewing a series of 10-gallon batches. “The beer was born at Seibel,” Fulbright says.

Fulbright graduated from the Siebel Institute in 1989. Now he had to find a place to brew. The obvious choice was the old Stevens Point Brewery just 70 miles northwest of Oshkosh. In 1990 The the 133-year-old Point Brewery was fighting for its life. It struggled to maintain the relevancy of its signature lager in a complex marketplace dominated by corporate behemoths and a slew of attention grabbing upstarts making trendy micro-brews. But the brewery had an adventurous Brewmaster named John Zappa and Fulbright’s plan for making a craft beer that recalled the glory days of Wisconsin brewing appealed to him. Fulbright made his final pilot brew of Chief Oshkosh Red Lager on November 21, 1990 at Siebel and submitted the recipe to Zappa. The following spring, they began to brew.

Making Fulbright’s idea a reality wasn’t cheap and it wasn’t easy. All of his resources were funneled into the production of the beer. “At first, I had to pay for everything upfront," Fulbright says. "I spent thousands getting it started.” In May of 1991, Fulbright and Zappa began brewing the beer in 100 barrel batches, each of them learning along the way. For Fulbright, large-scale production brewing was an altogether new experience while the brewers at Point had to adapt to imported malts and hops that the brewery hadn’t used before. Fulbright says he always oversaw the brewing of his beer. “I spent a lot of time up in Point and got to know John Zappa. I always considered his ideas, but he knew this was my beer. It was my formula.”

In June of 1991 Chief Oshkosh Red Lager hit the market. The first public tasting of the beer was held on Wednesday, June 19th at the Oshkosh Hilton. About 45 people were on hand to try the new beer and the following morning the Oshkosh Northwestern ran a photograph taken at the event showing Fulbright and Zappa joining in a toast with Fulbright's brewing mentor David S. Ryder. America's first Red Lager was born.

Initially the beer was sold only in cans. Mid-Coast Brewing was strapped for cash and cans were the least expensive packaging option, but Fulbright saw it as an opportunity. Early ads for the beer make a point of the fact that it was the only American all-malt beer to be packaged this way and asserted that cans offered better protection for the beer and were more environmentally friendly. Fulbright's ad copy from the period was prescient. Fifteen years later, the idea of craft beer in cans began to catch on and brewers now typically promote their canned beer using language that closely echos Fulbright's early arguments. But Fulbright may have been a little too far ahead of his time. Canned beer had a down-scale image in 1991. Trying to convince drinkers of premium beer that cans were the best way to preserve quality was a tough sell. “The idea that great beer doesn't come in a can hurt me,” Fulbright says.

In spite of that, the beer did well. The original retailers were clustered in Winnebago, Outagamie and Fond du Lac Counties and at $3.99 a six-pack it was pitched as a high-end beer at an affordable price. Six months after the beer was introduced Fulbright told the Milwaukee Journal, “We sold in three counties what we thought we’d sell in 13.” In addition to store sales the beer went on tap in a number of bars in Oshkosh including Oblio’s, the B & B Tap and the Pioneer Inn. It wasn’t always easy getting some of the older taverns in Oshkosh to take on the beer. “I went to all the taverns in town,” Fulbright says. “I’d go in and have some old-geezer tavern owner yelling at me ‘I can’t sell that dark shit!’”

As sales increased so did the beer’s recognition. Reviews of the Red Lager were mostly favorable with several noted beer writers weighing in. Michael Jackson, author of the New World Guide to Beer and the leading beer writer of his time, praised the beer for its “unapologetic, robust sweetness” and its “delicate hint of hop.” Homebrew guru and editor of Zymurgy Magazine, Charlie Papazian called it “a pleasantly great beer” and Mike Bosak, editor of All About Beer Magazine, wrote that the beer was “just delightful.” Beer aficionados weren’t the only people taking note. A number of breweries and brew-pubs glommed onto Fulbright’s idea and within a year of Chief Oshkosh Red Lager’s introduction there were more than a dozen other Red Lagers being sold in America.

Meanwhile, Fulbright continued to push his beer. In early 1992 he struck a deal with Beer Capitol Distributing who brought the beer into Milwaukee. The beer was now being sold throughout the state and in June of 1992 became available in bottles. Fulbright used the National Micro-and Pubbrewers Conference that year to introduce his new bottle saying “The new package will properly establish the correct, quality image for this hand-crafted, all-malt beer.” With production ramped up to 2,000 barrels for the year, Fulbright had his work cut out for him. From the start, Mid-Coast Brewing was a one-man operation and Fulbright liked it that way. He did all the promotion, took care of the accounts, oversaw the brewing and negotiated his own distribution agreements. “I was a one man band,” Fulbright says. You can see his mark on everything identified with Mid-Coast Brewing. Newspaper and magazine ads for the beer were written by Fulbright and they stood in stark contrast to the promotions of other brewers. The ads were serious and wordy and usually tagged with Fulbright’s signature. The back of the cans and bottles featured a detailed description of the beer and its connection to the history of brewing in Oshkosh along with Fulbright’s invitation to try his beer. Fulbright had carved out an identity for his beer that was as much his own as that of the history his beer referenced.

By 1993 Chief Oshkosh Red Lager was poised to become one of the nation’s most well-known micro-brews. In January, Fulbright made an agreement with Western International Imports of Chicago to market his beer nationally. Fulbright said at the time, "This partnership will give Chief Oshkosh the kind of backing that should make this beer a major player in the microbeer segment.” Western International wanted a Midwestern micro-brew that they could make big and planned to position Fulbright’s beer as the Midwestern equivalent of Samuel Adams Boston Lager. They launched an ambitious campaign to distribute the beer and within months, Chief Oshkosh Red Lager became the most widely distributed beer ever to be based in Oshkosh. But the new partnership made it necessary for Fulbright to relinquish control over the distribution of his beer. The agreement allowed Western International to order beer directly from the Point brewery and Fulbright soon found it difficult to keep up with the additional expenses associated with the increased production needed to fill the orders.

It wasn't just money woes Fulbright was forced to contend with. In 1992 David S. Ryder, the Siebel instructor who had helped Fulbright develop his beer, went to work for Miller Brewing. A year later, Miller subsidiary Leinenkugel Brewing brought out a Red Lager that was extraordinarily similar to the beer Fulbright was making. "You could hardly tell the difference between the two beers," Fulbright says. Worse yet, Leinenkugel had access to Miller's massive distribution network. The squeeze was on.

Fulbright battled back by trying to expand the Mid-Coast portfolio. He planned for a series of draught-only beers that would include an Oatmeal Stout, a Dopplebock and a Bavarian Dunkel and in late 1993 he began brewing Munich Gold, a German Helles beer. "I really liked the Munich Gold," Fulbright says. "I really thought it was a good beer and a last shot at expansion. It was a last ditch effort to keep the brand alive." And though Chief Oshkosh Red Lager continued to gain acceptance, winning a silver medal at the 1994 World Beer Championships, market pressure grew more intense. Leinenkugel's Red Lager was now being sold throughout the United States and Fulbright was finding it increasingly difficult to compete. "When Leinenkugel's moved in, my distributors lost interest in my beer," Fulbright says. "We started getting killed. It was a tsunami."

The competition proved to be too much. By late 1994 Mid-Coast Brewing had exhausted its capital and though Fulbright continued to fight, the battle was essentially over. "Basically we ran out of money," Fulbright says. "I tried to be as aggressive as possible with no money, but we were in our death throes. It was a struggle against big business. The big guy won. We didn’t stand a chance."

On December 30, 1994 the last batch of Chief Oshkosh Red Lager was brewed. It was a 200 barrel brew and sales of that beer continued on through the first half of 1995. Then it was gone. And with it went Fulbright's hope of one day building a new brewery for his beer in Oshkosh.

Still, it was an incredible experience for Fulbright and if he's bitter about how it all came out, he certainly doesn't show it. If he has a regret it appears to be this: "I only wish more people knew how much effort went into it. This thing wasn’t as simplistic as most people think it was. This wasn't just some contract beer. I stuck everything I had into it. There was real effort and real thought put into making a good beer. I gave it everything."

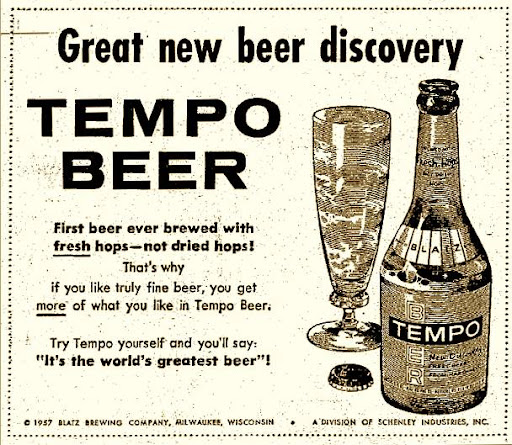

The hop harvesting season is nearly upon us in Oshkosh and there'll soon be a few local homebrewers making beer with hops they've plucked fresh from the vine. Well, that ain't nothin' new. This is an advertisement that ran in the Oshkosh Northwestern on July 10, 1957 and it claims that Tempo was the first beer to be brewed with fresh hops, as opposed to the dried hops brewers typically use. That's wrong. The first people to stumble upon the realization that hops added something good to their brews certainly hadn't gone to the trouble of drying them out. That came later. Truth be damned, it remains impressive that Blatz was marketing a wet-hopped beer here in Oshkosh more than 50 years ago. But you've got to wonder just how "fresh" those hops could have been. They were selling this beer in July, hardly the time of year for fresh hops in Wisconsin. The problem is, fresh hops don't hold up very well. You need to go from the hop plant to the kettle in just a few hours. If you miss that window of opportunity your beer ends up tasting as if you brewed it with lawn clippings. Still, you've got to admire the Blatz chutzpah. How many brewers these days would dare to run an advertisement for their beer claiming "It's the world's greatest beer"! By the way, there's an excellent beer bar in Milwaukee named the Bomb Shelter that supposedly has an old bottle of this floating around in their collection. Unfortunately, I've heard it's empty. But of course, it’s empty. You wouldn't expect the world's greatest beer to have gone unopened, would you?

The hop harvesting season is nearly upon us in Oshkosh and there'll soon be a few local homebrewers making beer with hops they've plucked fresh from the vine. Well, that ain't nothin' new. This is an advertisement that ran in the Oshkosh Northwestern on July 10, 1957 and it claims that Tempo was the first beer to be brewed with fresh hops, as opposed to the dried hops brewers typically use. That's wrong. The first people to stumble upon the realization that hops added something good to their brews certainly hadn't gone to the trouble of drying them out. That came later. Truth be damned, it remains impressive that Blatz was marketing a wet-hopped beer here in Oshkosh more than 50 years ago. But you've got to wonder just how "fresh" those hops could have been. They were selling this beer in July, hardly the time of year for fresh hops in Wisconsin. The problem is, fresh hops don't hold up very well. You need to go from the hop plant to the kettle in just a few hours. If you miss that window of opportunity your beer ends up tasting as if you brewed it with lawn clippings. Still, you've got to admire the Blatz chutzpah. How many brewers these days would dare to run an advertisement for their beer claiming "It's the world's greatest beer"! By the way, there's an excellent beer bar in Milwaukee named the Bomb Shelter that supposedly has an old bottle of this floating around in their collection. Unfortunately, I've heard it's empty. But of course, it’s empty. You wouldn't expect the world's greatest beer to have gone unopened, would you?