|

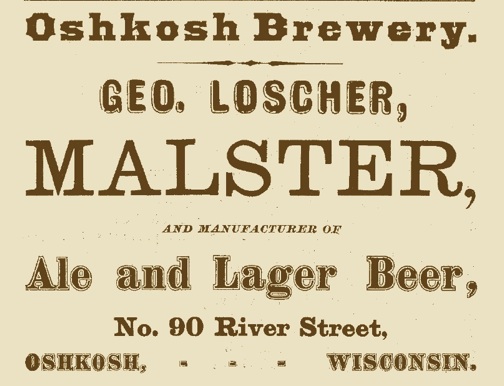

| 1858 Map of Oshkosh Showing Location of Lake Brewery |

The long-forgotten cradle of Oshkosh brewing is now occupied by an unassuming ranch-style home just south of Ceape Avenue at 74 Lake Street. Here is where a German immigrant named Jacob Konrad, who purchased the land in July of 1849, established Oshkosh’s first commercial brewery. And though Konrad would leave Oshkosh by the mid-1850s, the incredible lineage of his brewery would extend to 1972 and the closing of Oshkosh’s last full-scale, production brewery.

The earliest days of what came to be known as the Lake Brewery have been obscured by time, but the picture begins to clear in 1854 when Jacob Konrad sold his brewery to a lively German émigré named Anton Andrea. Born in Frankfurt in 1822 and educated in Switzerland, Andrea became a Major in the Hungarian Hussars and was forced to fight against his native country when Hungary revolted against Austrian rule in 1848. Andrea turned fugitive, fled to Turkey and made his way to Constantinople where he embarked on a ship bound for America. In 1849 he arrived in Oshkosh.

Andrea’s 30 years in Oshkosh would prove to be as picaresque as his life in Europe. He was elected to the first Oshkosh City Council in 1853, made and lost several fortunes, was burned out on six occasions, and at one time or another sold everything from groceries to clothes to liquor to real-estate. Ironically, the one thing Andrea may not have done was brew beer. Andrea didn’t come from brewing background and unlike the Oshkosh brewmasters of the period, he didn’t live at the brewery. The 1857 Oshkosh city directory shows two other brewers, Casper Haberbusch and Louis Keller, working at the Lake Brewery during the time it was under Andrea’s name, indicating that this may have been the first brewery in Oshkosh where the beer was made by someone other than the man who owned the brewhouse.

What is certain is that by 1862 Andrea’s role at the brewery was tangential at best. That year, Andrea leased the Lake Brewery to a 35-year-old brewer trained in Saxony named Leonhardt Schwalm. Schwalm’s tenure at the brewery was even more brief than that of his predecessors. In September of 1865 his lease on the Lake Brewery expired and in October Schwalm bought a parcel of land on Doty Street where he and August Horn established Horn and Schwalm’s Brooklyn Brewery. Incidentally, that same tract would later be home to the Oshkosh Brewing Company.

Meanwhile, a new brewer had occupied the Lake Brewery. Immediately upon Schwalm’s removal, the brewery was taken over by a 30-year-old German-born butcher from Stevens Point named Gottlieb Ecke. With the backing of a short-term business partner named Edward Becker, Ecke assumed control of the brewery in September of 1865 and a month later purchased it outright from Andrea. Along with the purchase of the brewery, Ecke also acquired from Andrea several lots west of the brewery on Harney Avenue. Ecke was looking to the future.

An inventory of the brewery from 1865 reveals a dated facility geared to meet the the needs of an earlier era. Not only had brewing methods rapidly progressed in the intervening years, Oshkosh had as well. The Lake Brewery came into being at a time when Oshkosh’s population barely exceeded 2,000 people. By the end of the 1860s Oshkosh had over 12,000 residents and if Ecke was going to keep pace, he’d need an updated, more efficient brewhouse.

In 1868 Ecke began setting up a new brewery a block west of the original Lake Brewery on the additional lands he had purchased from Anton Andrea. The brewery was located in the area that now falls within the addresses of 1239-1247 Harney Avenue and was fully operational by 1869. Unfortunately, death would soon intervene. Just two years after the completion of his brewery, Gottlieb Ecke died on a Sunday night in November of 1871. He was 37 years old. Oddly, the circumstances of Ecke’s death went unreported in the three Oshkosh newspapers then in publication. The only notice of his passing appeared in the Oshkosh Times, which printed a two-line obituary that failed to even include his full name, listing him simply as G. Ecke.

Ecke left behind a wife, four young children and a mountain of debt taken to finance construction of the new brewery. A brewery which appears to have remained idle for the next year. Unable to keep the business running, Charlotte Ecke, the widow of Gottlieb Ecke, was forced to sign over possession of the brewery to her late husband’s principle creditor in March of 1874.

|

| Lorenz Kuenzl |

If there was any good that came from the rapid dissolution of the Ecke brewery, it was that the man who assumed Ecke’s place in the brewhouse would prove to be the most accomplished of the early Oshkosh brewers. Lorenz Kuenzl was born in Bohemia (now the Czech Republic) in 1845 where, at an early age, he became an adept in the art and science of brewing beer. Kuenzl came to America in 1871 and made his way to Stevens Point where the 31-year-old brewer married a 21-year-old Barbara Walter. Kuenzl was probably in Oshkosh by the close of 1874 and the following year took over the Ecke brewery with the help of his brother-in-law, John Walter.

The Oshkosh brewing scene of the mid-1870s was an embarrassment of riches. In 1875 there were six breweries in Oshkosh, four of them north of the river, and though the population of Oshkosh was rapidly gaining, a brewery looking to carve a niche for itself needed something special. Lorenz Kuenzl fit the bill.

Kuenzl christened his enterprise the Gambrinus Brewery in honor of King Gambrinus, the patron saint of brewers, and quickly established a reputation as a maker of quality beer. Although the Gambrinus Brewery would soon be outpaced in terms of production by the rapidly expanding Oshkosh breweries south of the Fox River, no other Oshkosh brewery could claim the variety of beer that Kuenzl produced. Kuenzl targeted his output to that segment of the Oshkosh populace longing for the lagers of their German homeland. Among the beers in the Gambrinus line-up were a malty Vienna lager; a Bohemian lager that emphasized hops; and a full-bodied, dark lager familiar to the Kulmbach region of Bavaria. Kuenzl knew his audience and confined the lion’s share of his advertising for the Gambrinus Brewery to the Wisconsin Telegraph, Oshkosh’s German language newspaper. The ads were simple and direct with Kuenzl’s name featured prominently beneath that of his brewery followed by a brief list of the current brews. Obviously, Kuenzl was addressing people well acquainted with stylistic differences among beers. No further explanation was required.

Though his ability as a brewer may have been a match for the quality he desired, Kuenzl’s funds were apparently not the equal of either. Kuenzl and Walter lacked the capital to purchase the brewery outright so instead leased the property from Henry Timm, a carpenter living at what is now 621 Ceape Avenue. Timm was a friend of the Ecke family and had purchased the brewery immediately after Charlotte Ecke had lost it to foreclosure. The relationship between Kuenzl and his landlord would prove to be sometimes contentious, but the atmosphere inside the brewery was familial, to say the least. Along with his brother-in-law John Walter, Keunzl’s brother Andrew also worked at the brewery and in 1879 Gottlieb Ecke’s now 16 year-old son, Otto, went to work alongside the Gambrinus crew in the brewhouse his father had built.

With the start of a new decade, though, things at the brewery began to change. In May of 1880, Kuenzl and John Walter dissolved their partnership, but more significantly, Kuenzl now found himself facing a competitive disadvantage. Although the Gambrinus Brewery was relatively new, its capacity was dwarfed by two new brewhouses on the South Side of Oshkosh. Both John Glatz’s Union Brewery and the Brooklyn Brewery of Horn & Schwalm had recently been rebuilt and each was capable of producing three times the quantity of beer Kuenzl could make. Worse yet was the new threat posed by the enormous breweries of Milwaukee now sending train cars full of beer into Oshkosh in an attempt to claim the market for their own.

As other small Oshkosh breweries began to fade, Kuenzl somehow managed to hold on. Although limited by the constraints of his brewery, Kuenzl continued brew to his own standards and in 1883, under threat of eviction, raised enough capital to purchase the brewery from Henry Timm. Lorenz Kuenzl had finally made The Gambrinus Brewery his own.

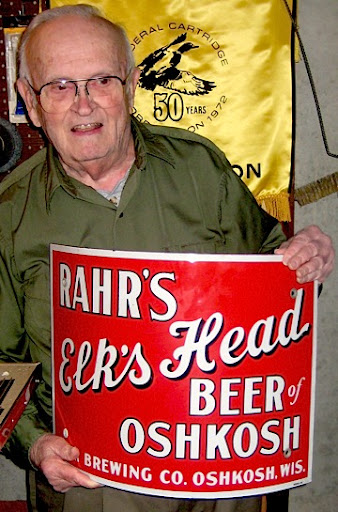

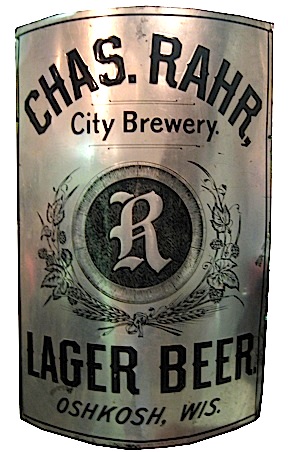

For the next 11 years things remained just that way. Then came 1894. Battered by a disastrous economic slump and their relentless adversaries from Milwaukee, Oshkosh’s three leading brewers - Horn & Schwalm, John Glatz, and Lorenz Kuenzl - joined forces to form the Oshkosh Brewing Company. The conglomeration would result in the largest, best-known brewery Oshkosh would ever know. Although, Kuenzl’s brewery was by far the smallest of the three, his influence on the new company would be disproportionate to his share of the firm’s assets. Kuenzl was named superintendent of the Oshkosh Brewing Company and it’s clear from the early roster of beers it produced that Lorenz Kuenzl was responsible for establishing the new company’s brewing regimen.

With the formation of the Oshkosh Brewing Company, the Gambrinus Brewery was converted into a bottling facility. Three years later, Lorenz Kuenzl died at the age of fifty-three due to complications of edema. Following the construction of the Oshkosh Brewing Company’s new brewery in 1911, The Gambrinus Brewery was dismantled and the surrounding property sold as residential lots.

What began as Oshkosh’s first brewery on Lake Street and later evolved into the breweries of Ecke and Kuenzl helped form the basis for what became Oshkosh’s premier brewery. When the Oshkosh Brewing Company folded in 1971, its signature brands were assumed by the Peoples Brewing Company, the last of Oshkosh’s large-scale breweries. A lineage that joins 123 years of brewing history in our city had reached its conclusion.