Here’s something to make the new year a little happier: The most recent batches of Central Waters Brewers Reserve barrel series were packaged on December 14th and now they’ve arrived in Oshkosh. At Festival Foods in Oshkosh they have both the Bourbon Barrel Stout and the Bourbon Barrel Cherry Stout on the shelves waiting to be taken home and made part of your inner being. If you enjoy barrel aged beers, these are a couple that you shouldn’t miss. They’re aged in re-purposed, oak, bourbon barrels for up to 6 months resulting in big, smooth imperial stouts haunted by an undercurrent of bourbon. For the Cherry Stout they load eighty pounds of tart Door County Cherries into each barrel resulting in a beer that’s incredibly complex and surprisingly refreshing.

Check out the labels on these beers. Something has gone awry, here. Though the bottling date for each is marked as December of this year, the one is sporting a 2010 neck band while the other shows 2011. Misprint or left-over labels? Who cares! These are going for $10.99 a 4-pack at Festival and though they’ve got a pretty good stash it probably won’t last. Barrel on!

Thursday, December 30, 2010

Tuesday, December 28, 2010

John Glatz and the Union Brewery of Oshkosh

|

| John Glatz |

Upon arriving in America, Glatz went to Cincinnati. Its large German population and booming beer scene would have seemed a natural fit for an ambitious, 23-year-old brewer. But after three years of making beer there, Glatz was on the move again. He spent six months brewing in Philadelphia and then in 1857 went to Milwaukee where beer was becoming an essential element of the burgeoning city. For a time, Glatz appeared to have found his niche. He settled in as foreman of a South Side brewery and in 1861 the 32-year-old Glatz took a 19-year-old bride named Louisa Elser. The brewer from Baden had established a comfortable living. After 12 years of brewing someone else’s beer, though, Glatz wanted a brewery of his own. He found the opportunity he was looking for in Oshkosh.

In 1869 there was a new brewery in waiting at the south end of Doty Street. It had been built by Franz Wahle, who in 1857 had founded the Stevens Point Brewery. After selling the Point Brewery in 1867, Wahle moved to Oshkosh and began construction of the new brewhouse that would become the Union Brewery and the new home of the John Glatz family.

John and Louisa Glatz now had three children and shortly after moving into the brewery they were joined by Christian Elser, his wife Anna and their three children. In all probability, Elser was the older brother of Louisa Glatz, but he wasn’t just family, he was an experienced brewer, as well. The German-born Elser was 29 and prior to coming to Oshkosh had brewed at the Bavarian Brewery in Wauwatosa under the tutelage of Franz Falk, a master brewer from Bavaria. With almost 40 years of experience between them, Glatz and Elser were a significant addition to Oshkosh’s flourishing community of brewers.

When the Union Brewery went into operation in 1869 it became one of six Oshkosh breweries and within their first year Glatz and Elser produced a respectable 500 barrels of beer. The Oshkosh beer market was expanding and Glatz and Elser were poised to take a sizable portion of it, but first they’d be dealt a disastrous set-back. At 10 p.m. on a cold Friday in early December of 1871 the brewery that Wahle built caught fire. Firefighters soon arrived, but were unable to draw water. They watched as the Union Brewery burned to the ground.

|

| The Union Brewery 1886 |

At the time of the fire Franz Wahle owned the brewery, but Glatz and Elser had insured the business for $6,000. When their claim came through in January of 1872, Glatz and Elser purchased the ruins of the brewhouse and the four acres of land surrounding it from Wahle for $5,400 - a figure that would today amount to about $135,000. And then they started all over again.

This time there would be no deterring them. In 1872 Glatz and Elser rebuilt the brewery and over the next five years more than tripled their original output. Though their methods were informed by centuries of German brewing practice, theirs was truly an Oshkosh beer made with locally grown hops and grain that Glatz himself malted at the brewery. Success came early and by 1878 they were making more beer than any other brewery in Oshkosh, producing over 1,500 barrels a year. An impressive figure considering the size of their market (Oshkosh’s population was then just 14,876) and the seasonal limitations faced by lager brewers in the years before mechanical refrigeration was commonplace. Oshkosh was quickly becoming a regional force in Wisconsin brewing and Glatz and Elser were leading the way.

Production continued to increase and in 1879 the Union Brewery surpassed its previous year’s effort by more than 100 barrels. But 1879 was also a pivotal year for the Union Brewery. In the fall of that year, Glatz and Elser dissolved their partnership and on November 7, 1879 Elser sold his interest in the brewery to Glatz for $13,000; a sum that would be worth about $288,000 today. Elser would go on to establish a meat market and beer bottling business on 18th Avenue between Doty and Oregon and Glatz kept right on brewing. He had eight employees working for him now, not including his son William, who at 17 would have certainly been old enough by his father’s standard to become immersed in the business of making beer.

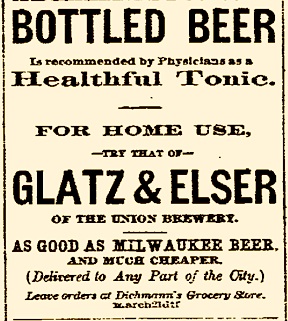

The Oshkosh beer market, though, was changing rapidly. When the Brooklyn Brewery, just up the street on Doty, burned down in 1879, August Horn and Theodore Schwalm built a larger brewery in its place that would soon outpace the production of Glatz’s plant. But more troubling than the local competition was the “foreign” beer being brought in from Milwaukee. The Milwaukee brewers, Pabst and Schlitz in particular, had capacity advantages, which allowed them to flood growing markets such as the one in Oshkosh, making it difficult for local brewers to compete. Glatz battled back. He struck a deal with William Dichmann, proprietor of the leading grocery on Main Street, to distribute his beer and dramatically increased the capacity of his small brewery, eventually plateauing at an incredible 30,000 barrels a year. Glatz also began producing a series of to-the-point advertisements that never failed to include the lines, “As good as Milwaukee beer. And much cheaper.” It was a well-aimed retort coming from a man who had spent more than 12 years of his life brewing “Milwaukee beer”.

Glatz continued on as the sole owner of the Union Brewery until 1888. On May 1st of that year, he made his 25-year-old son, William, a full partner in the business. John Glatz was now 59 years old. His brewing career was nearing its end, but not before he would influence the next stage in Oshkosh’s development as a brewing center. In 1894 Glatz merged his Union Brewery with Horn and Schwalm’s Brooklyn Brewery and Lorenz Kuenzl’s Gambrinus Brewery to form the Oshkosh Brewing Company. Glatz was named vice president of the new company. His son William, who ten years later would become president of Oshkosh Brewing, was appointed treasurer. On April 12, 1894 John and Louisa Glatz deeded their brewery to the Oshkosh Brewing Company for $78,000, an amount that would now equal just over 2 million dollars. A year later, on April 25, 1895, John Glatz died at the age of sixty five.

The Union Brewery remained operational until 1915 when it was dismantled and its production moved to the large, modern brewery built by the Oshkosh Brewing Company on Doty Street in 1911. In 1976, the site of the brewery was bought by the city of Oshkosh and re-named Glatz Park. Today there’s little there to suggest the dynamism that characterized the years when the Union Brewery was running full tilt. The park is unmarked and mostly left untended. All that is left of the brewery are the outcroppings of the lagering caves that were at the foundation of the brewhouse.

|

| Remains of Union Brewery Caverns 1975 |

|

| The Home of John Glatz 1894 & 2010 |

Friday, December 24, 2010

Wednesday, December 22, 2010

The Dark Season

Yesterday afternoon at 5:38 pm we reached the winter solstice. The darkest part of the year is here and there’s nothing that brightens these short, black days better than a big, black beer. It’s time to go opaque.

Let’s start over at Fratellos' Fox River Brewing Company where they’re making something of a secret of the fact that this December marks their fifteenth year of brewing in Oshkosh. They’ve just resurrected the venerable Titan Porter, though, and it’s a proper companion for wondering where the hell all that time went. This is a porter in a rich and robust vein with a great aroma of toast on the verge of scorching. A healthy dollop of coffee and chocolate follow through in the quaff and it closes with a dry, dark-malt and hop bitterness that lingers until the next pull. Get it while you can.

At Festival Foods in Oshkosh, they’ve recently stocked up on a couple of worthy black beers. The Guinness Foreign Extra Stout is an odd, little ale that’s nothing like that other Guinness Stout you know about. When I say little, I mean that annoying European practice of sending us beer in 11.2 oz bottles instead of giving us the full 12. Aside from that, this beer is big enough at 7.5% and is heartier than you’d expect any breed of Guinness to be. Lot’s of smoky, charred malt aroma smolders off this one and the flavor comes on with a carbonic shot of burnt grain and bitter hops. The hop aspect of this surprised me; it’s almost American in execution. I don’t know that I’d make a habit of this beer, but it’s definitely one to seek out and experience.

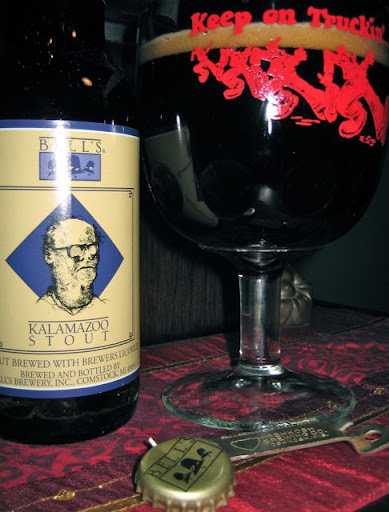

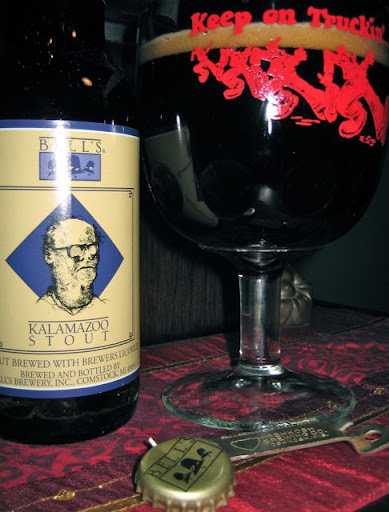

And just in at Festival, all the way from trusty and rusty Kalamazoo, is our old friend Bell’s Kalamazoo Stout. This brew tends to come and go around here, but right now there’s a fresh batch waiting to get reacquainted with your liver. This is one of those comfortable stouts that’s easy to take for granted until you start drinking and remember all over again what a fine beer it is. The beer comes with all the standard, American stout features. It’s roasty and peaty and a little sweet with a nice zip of hops and it’s all balanced so well that only a dolt would miss it’s deliciousness. Ummmm.

And just in at Festival, all the way from trusty and rusty Kalamazoo, is our old friend Bell’s Kalamazoo Stout. This brew tends to come and go around here, but right now there’s a fresh batch waiting to get reacquainted with your liver. This is one of those comfortable stouts that’s easy to take for granted until you start drinking and remember all over again what a fine beer it is. The beer comes with all the standard, American stout features. It’s roasty and peaty and a little sweet with a nice zip of hops and it’s all balanced so well that only a dolt would miss it’s deliciousness. Ummmm.

All right, one last beer for those among us afraid of the dark. Festival now has New Belgium’s Frambozen Raspberry Brown Ale, a fruit beer that skips down the same lane as New Glarus’ Raspberry Tart. Frambozen isn’t going to blow you away with the sort of succulent unctuousness of the Tart, but it’s no slouch and one to put on your list if fruit beers with a Belgian slant are your thing. Also, the aroma and color is quite un-beer like, so if you’re having one of those days you could probably get away with drinking this at work. Just an idea.

All right, one last beer for those among us afraid of the dark. Festival now has New Belgium’s Frambozen Raspberry Brown Ale, a fruit beer that skips down the same lane as New Glarus’ Raspberry Tart. Frambozen isn’t going to blow you away with the sort of succulent unctuousness of the Tart, but it’s no slouch and one to put on your list if fruit beers with a Belgian slant are your thing. Also, the aroma and color is quite un-beer like, so if you’re having one of those days you could probably get away with drinking this at work. Just an idea.

Let’s start over at Fratellos' Fox River Brewing Company where they’re making something of a secret of the fact that this December marks their fifteenth year of brewing in Oshkosh. They’ve just resurrected the venerable Titan Porter, though, and it’s a proper companion for wondering where the hell all that time went. This is a porter in a rich and robust vein with a great aroma of toast on the verge of scorching. A healthy dollop of coffee and chocolate follow through in the quaff and it closes with a dry, dark-malt and hop bitterness that lingers until the next pull. Get it while you can.

At Festival Foods in Oshkosh, they’ve recently stocked up on a couple of worthy black beers. The Guinness Foreign Extra Stout is an odd, little ale that’s nothing like that other Guinness Stout you know about. When I say little, I mean that annoying European practice of sending us beer in 11.2 oz bottles instead of giving us the full 12. Aside from that, this beer is big enough at 7.5% and is heartier than you’d expect any breed of Guinness to be. Lot’s of smoky, charred malt aroma smolders off this one and the flavor comes on with a carbonic shot of burnt grain and bitter hops. The hop aspect of this surprised me; it’s almost American in execution. I don’t know that I’d make a habit of this beer, but it’s definitely one to seek out and experience.

And just in at Festival, all the way from trusty and rusty Kalamazoo, is our old friend Bell’s Kalamazoo Stout. This brew tends to come and go around here, but right now there’s a fresh batch waiting to get reacquainted with your liver. This is one of those comfortable stouts that’s easy to take for granted until you start drinking and remember all over again what a fine beer it is. The beer comes with all the standard, American stout features. It’s roasty and peaty and a little sweet with a nice zip of hops and it’s all balanced so well that only a dolt would miss it’s deliciousness. Ummmm.

And just in at Festival, all the way from trusty and rusty Kalamazoo, is our old friend Bell’s Kalamazoo Stout. This brew tends to come and go around here, but right now there’s a fresh batch waiting to get reacquainted with your liver. This is one of those comfortable stouts that’s easy to take for granted until you start drinking and remember all over again what a fine beer it is. The beer comes with all the standard, American stout features. It’s roasty and peaty and a little sweet with a nice zip of hops and it’s all balanced so well that only a dolt would miss it’s deliciousness. Ummmm. All right, one last beer for those among us afraid of the dark. Festival now has New Belgium’s Frambozen Raspberry Brown Ale, a fruit beer that skips down the same lane as New Glarus’ Raspberry Tart. Frambozen isn’t going to blow you away with the sort of succulent unctuousness of the Tart, but it’s no slouch and one to put on your list if fruit beers with a Belgian slant are your thing. Also, the aroma and color is quite un-beer like, so if you’re having one of those days you could probably get away with drinking this at work. Just an idea.

All right, one last beer for those among us afraid of the dark. Festival now has New Belgium’s Frambozen Raspberry Brown Ale, a fruit beer that skips down the same lane as New Glarus’ Raspberry Tart. Frambozen isn’t going to blow you away with the sort of succulent unctuousness of the Tart, but it’s no slouch and one to put on your list if fruit beers with a Belgian slant are your thing. Also, the aroma and color is quite un-beer like, so if you’re having one of those days you could probably get away with drinking this at work. Just an idea.

Tuesday, December 21, 2010

The Beers of Christmas Past

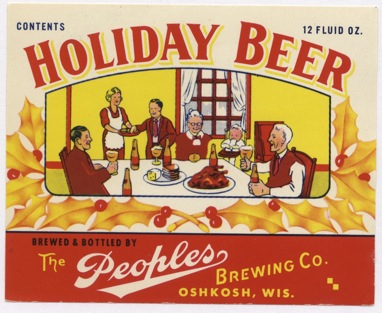

If you’re given to haunting the local beer depots you’ve undoubtedly noticed that the shelves are heavy with holiday beer these days. That’s nothing new in Oshkosh. Holiday beers have been a seasonal tradition here ever since the repeal of Prohibition in 1933. When full repeal arrived on December 5, 1933, both Peoples Brewing and the Oshkosh Brewing Company immediately released beer for the season that was stronger and more flavorful than their standard brews.

The seasonal beers soon became an important part of the breweries’ yearly output. Each year, sales of beer in Oshkosh would invariably fall-off with the end of summer and the Oshkosh brewers saw the holiday brews as a way to re-ignite the interest of beer drinkers during the slump of the cold months. It was a tradition that lasted almost 40 years.

Peoples Brewing described their Special Holiday Brew as a “High-Test Beer”. It a was full-bodied, higher-alcohol, lager brewed with Munich malt and aged for an extended period. The basic description of the beer would put it firmly within the Oktoberfest style. Down the street from Peoples Brewing, the Oshkosh Brewing Company made their Holiday Brew with a somewhat heavier body, yet lighter in color. Oshkosh Brewing boasted about the “warming” quality of the beer and its distinctive hop flavor. The beer was probably akin to what would be considered a Maibock or Helles Bock.

Unfortunately, all of those beers are gone. Now, all that’s left are the labels. Here’s to the beers of Christmas past.

The seasonal beers soon became an important part of the breweries’ yearly output. Each year, sales of beer in Oshkosh would invariably fall-off with the end of summer and the Oshkosh brewers saw the holiday brews as a way to re-ignite the interest of beer drinkers during the slump of the cold months. It was a tradition that lasted almost 40 years.

Peoples Brewing described their Special Holiday Brew as a “High-Test Beer”. It a was full-bodied, higher-alcohol, lager brewed with Munich malt and aged for an extended period. The basic description of the beer would put it firmly within the Oktoberfest style. Down the street from Peoples Brewing, the Oshkosh Brewing Company made their Holiday Brew with a somewhat heavier body, yet lighter in color. Oshkosh Brewing boasted about the “warming” quality of the beer and its distinctive hop flavor. The beer was probably akin to what would be considered a Maibock or Helles Bock.

Unfortunately, all of those beers are gone. Now, all that’s left are the labels. Here’s to the beers of Christmas past.

Monday, December 20, 2010

Beer for Christmas By Clarence "Inky" Jungwirth

Here's a different sort of beer story from our friend Inky Jungwirth

During World War II, I was a beer drinker and also a member of the 24th Infantry Division. On Oct. 20th, 1944, the 24th Infantry was involved in the Liberation of the Philippine Islands and the intial landing on the Island of Leyte. Fighting the Japanese on that island was fierce and there were many American casualties. Initially, supplies were scarce due to the large force of Americans engaged in the fighting, but by Christmas of 1944 equipment and supplies had been increased considerably and we were able to meet the enemy on a superior basis. Supplies had increased so that by Christmas Day every G.I, including all those in actual combat, were given a Christmas present by the U.S. Army. It was a case of Beer! The beer was warm as there was no way it could be refrigereated in the tropical climate of the Philippine Islands and though I don't remember the brand of beer, it was the best present a G.I. could receive.

Our beer was stored on trucks, away from the combat areas, with each man’s name attached to his case. There were times, during combat, when we were relieved for rest after days without any sleep and during these periods each man was allowed a bottle of beer from his case. Only one beer was permitted, though, to eliminate the temptation to become drunk and escape the horrors of combat. Although the beer was warm, we beer lovers were in seventh heaven to have the taste of even a warm bottle of beer.

Each man’s small allotment of beer was highly valued. While we were in the Philippines, we were given our monthly army pay in Peso's, but there was nothing to buy and, in a sense, the money you were paid was considered almost usless. Most of us were single men who figured our days were numbered. You might be killed tomorrow or next week. Gambling was a relief from the stress of combat and it was nothing for expert crap shooters to make thousands of dollars in Pesos in a night of gambling. What to do with that money? It was not unheard of for a beer loving gambler to pay a thousand dollars in Pesos for another soldier’s case of beer. Non-beer drinkers took a chance that they might survive the war and sent the money home to a bank account. Both the non-beer drinker and the gambler were happy.

Somewhere on the Island of Leyte, today, there must be thousands of beer bottles left behind by American G.I.s. All of them empty of beer, of course, as not a drop of beer was ever wasted or absorbed into the air. We G.I.s who survived the Philippine Island Liberation and the war in Leyte will remember the taste of that "Liquid Gold" and the Christmas of 1944 forever.

|

| Clarence "Inky" Jungwirth 1944 |

Our beer was stored on trucks, away from the combat areas, with each man’s name attached to his case. There were times, during combat, when we were relieved for rest after days without any sleep and during these periods each man was allowed a bottle of beer from his case. Only one beer was permitted, though, to eliminate the temptation to become drunk and escape the horrors of combat. Although the beer was warm, we beer lovers were in seventh heaven to have the taste of even a warm bottle of beer.

Each man’s small allotment of beer was highly valued. While we were in the Philippines, we were given our monthly army pay in Peso's, but there was nothing to buy and, in a sense, the money you were paid was considered almost usless. Most of us were single men who figured our days were numbered. You might be killed tomorrow or next week. Gambling was a relief from the stress of combat and it was nothing for expert crap shooters to make thousands of dollars in Pesos in a night of gambling. What to do with that money? It was not unheard of for a beer loving gambler to pay a thousand dollars in Pesos for another soldier’s case of beer. Non-beer drinkers took a chance that they might survive the war and sent the money home to a bank account. Both the non-beer drinker and the gambler were happy.

Somewhere on the Island of Leyte, today, there must be thousands of beer bottles left behind by American G.I.s. All of them empty of beer, of course, as not a drop of beer was ever wasted or absorbed into the air. We G.I.s who survived the Philippine Island Liberation and the war in Leyte will remember the taste of that "Liquid Gold" and the Christmas of 1944 forever.

Thursday, December 16, 2010

A Quick Fix of Six

If you don’t find yourself staring down a few good beers this weekend, it’ll be your own damned fault because there’s a lot of fine stuff flowing around town right now. Here’s a quick six of things you might want to make it your business to encounter.

If you don’t find yourself staring down a few good beers this weekend, it’ll be your own damned fault because there’s a lot of fine stuff flowing around town right now. Here’s a quick six of things you might want to make it your business to encounter. Over at Festival Foods they recently brought in a couple of succulent seasonals from Bell’s Brewing of lovely Kalamazoo. Bell’s Christmas Ale is an easy drinking, malty brew along the lines of a Scottish Ale that fairly glows in your cup. Nothing funny in the way of Christmas spices here, just a smooth, mellow beer with tasty notes of caramel malt. Then there’s Bell's Cherry Stout, a handsomely priced sipper that’s going for $12 and change. It’s a thick, chewy ale loaded with creamy malt and balanced by a burst of sharp and tart cherry juice. You probably won’t reach for a second bottle of this in the same session, but at 7% it’s a good buffer to these cold nights we’ve been having. Also at Festival, they recently brought out the 2010 Sierra Nevada Northern Hemisphere Harvest Ale. Here’s a wet-hop beer bitched-up with spicy hop flavor that snaps the backbone of malt they’ve tried to balance it with. Forget about balance, it’s the hops that make this beer. If you like the grassy, lemony flavor of fresh hops this ale will make you happy.

Over at Festival Foods they recently brought in a couple of succulent seasonals from Bell’s Brewing of lovely Kalamazoo. Bell’s Christmas Ale is an easy drinking, malty brew along the lines of a Scottish Ale that fairly glows in your cup. Nothing funny in the way of Christmas spices here, just a smooth, mellow beer with tasty notes of caramel malt. Then there’s Bell's Cherry Stout, a handsomely priced sipper that’s going for $12 and change. It’s a thick, chewy ale loaded with creamy malt and balanced by a burst of sharp and tart cherry juice. You probably won’t reach for a second bottle of this in the same session, but at 7% it’s a good buffer to these cold nights we’ve been having. Also at Festival, they recently brought out the 2010 Sierra Nevada Northern Hemisphere Harvest Ale. Here’s a wet-hop beer bitched-up with spicy hop flavor that snaps the backbone of malt they’ve tried to balance it with. Forget about balance, it’s the hops that make this beer. If you like the grassy, lemony flavor of fresh hops this ale will make you happy.Now for a couple brews you’ll need to belly up to the bar to gulp. At Fratello’s they have a Cream Ale pouring that’s more than the name implies. This isn’t one of those limp beers that tend to fall into this style, the Vixen Vanilla Cream Ale is a moderately robust winter seasonal with rich vanilla flavorings and just the right amount of heft at 5.9%. It’s a golden, hearty beer with a sweetish aroma that’s especially inviting. A good brew all the way around. At Becket’s they’ve had Hinterland's Winterland Porter going for a couple weeks now. Hinterland seems to be hitting their stride lately and this beer is another success for them. It starts with all the bold roastiness you’d expect in a winter porter and then it kicks in with a charge of very assertive piny hop flavors. It’s a surprising beer that ought to appeal to any hop-head.

Finally, and strictly for sentimental reasons, there’s that good, old Huber Bock that’s been pouring at O’Marro’s. Sure, you can go buy a 12-pack of this at a few of the local depots, but at O’Marro’s they’re serving it up in an old-fashioned jar-sort-of-mug that’s just right for this beer. I have a special affection for this lager as it was instrumental in triggering the beer geekery that still afflicts me. When I was way too young to drink legally I used to steal bottles of this from my old man’s stash. I loved every illicit sip of it. Never has such an unassuming beer tasted so great!

Tuesday, December 14, 2010

Brewing Chief Oshkosh Red Lager

It’s happening again. The river and lake are choking-up with ice and the snow is mounded in every open space. To the early brewers of Oshkosh, these were heartening signs. It meant the new lager season was here. It was time to start making the cold-fermenting beers they had been trained to brew in their European homeland.

A hundred some years later, there are plenty of area homebrewers still taking their cues from the weather. When the air turns frigid, many of the old basements in Oshkosh hit temperatures in the 50 degree range, perfect for fermenting that good, old lager beer. And here’s a recipe for lager beer that ties all of it together.

Chief Oshkosh Red Lager was a modern beer that recalled the earlier days of brewing in Oshkosh. The last batch of the beer was brewed 16 years ago, in December of 1994, and it’s about time we bring it back. The beer was essentially a Vienna Lager with an interesting twist that made it quite different from the premium lagers of the period. There were no other lagers of the time making such liberal use of Belgian specialty malts, which gave the beer a distinctively rich malt flavor and red hue while maintaining a medium body.

The recipe below is the homebrew version of the beer based upon the final pilot batches Jeff Fullbright brewed at the Siebel Institute in November of 1990. If you want to go all the way with this beer, you’ll need to Krauesen it, but for those of us who don’t adhere to the Reinheitsgebot a basic carbonation of 2.0-2.5 volumes will do just fine. Let’s brew it!

Chief Oshkosh Red Lager

Boil Volume: 7 Gallons

Batch Size: 5 Gallons

Single-step infusion Mash at 152º

60 Minute Boil

OG: 1.048

FG: 1.012

IBU: 19

SRM: 11

ABV: 4.6%

Grain Bill

American Six-row Pale: 5.25 lbs (58.7%)

American Two-row Pale: 3.0 lbs (33.6%)

Belgian CaraMunich: 8 oz (5.6%)

Belgian Special B: 3 oz (2.1%)

Hops

.4 oz Willamette Pellet hops (55 Minute Boil Time)

.2 oz Czech Saaz Pellet hops (55 Minute Boil Time)

.2 oz Willamette Pellet hops (30 Minute Boil Time)

.1 oz Czech Saaz Pellet hops (30 Minute Boil Time)

.2 oz Willamette Pellet hops (At flame out)

.1 oz Czech Saaz Pellet hops (At flame out)

Yeast/Fermentation

Wyeast 2035 North American Lager Yeast

Ferment at 48º-58º

When Primary Fermentation is complete, rack to secondary and lager at 10º cooler than your average fermentation temperature for an addition two-four weeks.

A hundred some years later, there are plenty of area homebrewers still taking their cues from the weather. When the air turns frigid, many of the old basements in Oshkosh hit temperatures in the 50 degree range, perfect for fermenting that good, old lager beer. And here’s a recipe for lager beer that ties all of it together.

Chief Oshkosh Red Lager was a modern beer that recalled the earlier days of brewing in Oshkosh. The last batch of the beer was brewed 16 years ago, in December of 1994, and it’s about time we bring it back. The beer was essentially a Vienna Lager with an interesting twist that made it quite different from the premium lagers of the period. There were no other lagers of the time making such liberal use of Belgian specialty malts, which gave the beer a distinctively rich malt flavor and red hue while maintaining a medium body.

The recipe below is the homebrew version of the beer based upon the final pilot batches Jeff Fullbright brewed at the Siebel Institute in November of 1990. If you want to go all the way with this beer, you’ll need to Krauesen it, but for those of us who don’t adhere to the Reinheitsgebot a basic carbonation of 2.0-2.5 volumes will do just fine. Let’s brew it!

Chief Oshkosh Red Lager

Boil Volume: 7 Gallons

Batch Size: 5 Gallons

Single-step infusion Mash at 152º

60 Minute Boil

OG: 1.048

FG: 1.012

IBU: 19

SRM: 11

ABV: 4.6%

Grain Bill

American Six-row Pale: 5.25 lbs (58.7%)

American Two-row Pale: 3.0 lbs (33.6%)

Belgian CaraMunich: 8 oz (5.6%)

Belgian Special B: 3 oz (2.1%)

Hops

.4 oz Willamette Pellet hops (55 Minute Boil Time)

.2 oz Czech Saaz Pellet hops (55 Minute Boil Time)

.2 oz Willamette Pellet hops (30 Minute Boil Time)

.1 oz Czech Saaz Pellet hops (30 Minute Boil Time)

.2 oz Willamette Pellet hops (At flame out)

.1 oz Czech Saaz Pellet hops (At flame out)

Yeast/Fermentation

Wyeast 2035 North American Lager Yeast

Ferment at 48º-58º

When Primary Fermentation is complete, rack to secondary and lager at 10º cooler than your average fermentation temperature for an addition two-four weeks.

Thursday, December 9, 2010

Christmas Cheer on Tap in Oshkosh

Anderson Valley’s Winter Solstice is pouring at Becket’s and Alpha Klaus is on tap at Oblio’s, setting them apart by just a few blocks geographically as well as spiritually. Both are medium bodied ales that deliver a load of flavor with a significant hop finish, but they each take a different path getting there.

Winter Solstice, at Becket’s, is the more traditional of these holiday brews. The aroma is close to Christmas cookies with ginger and nutmeg drifting up. The beer is semi-sweet and rich with a sticky, caramel malt flavor that builds as you drink it. And then comes a nice, smooth bitterness. At the very end all that rich, sweetish malt gets peeled away with a refreshing wash of bitter hops. It works as a great contrast to what came before it and makes the beer eminently drinkable. This is an excellent brew and at 6.9% it’s a fine match for the cold weather.

Meanwhile, over at Oblio’s, there’s Alpha Klaus - just the sort of beer you’d expect from Three Floyds. Lotsa hops and great brewing make them one of the most dependable breweries in America and their Christmas porter is everything it promises to be. The thing pours like liquified black chocolate and the aroma is enough to make you thankful for the smoking ban. Plenty of brown sugar and ground coffee in the nose of this beer and it’s all brought along on a clean breeze of piney, Christmas-tree smelling hops. I’m guessing there’s a fat dose of Challenger hops in this one because that evergreen flavor shoots all through it. The first few gulps bring a nice mix of caramel and roasted malts, but as you continue to drink those hops take over and the beer veers into IPA territory. This is a fun one and you’ll continue to taste it when you move on to your next as those hops keep working your palate. It’s the beer that keeps on giving. Who said Christmas is for kids?

Wednesday, December 8, 2010

Have a Beer with the Real Beer Man

Back in the early 90s, when Euro-brews such as Heineken were what passed for good beer in Oshkosh, a strange man came to town to help us chart our way out of the light-lager doldrums that had gripped this city for more than 40 years. That man was Jim Lundstrom. In 1991 he was a founding member of the Society of Oshkosh Brewers and, as a reporter for the Oshkosh Northwestern, was one of the first people in Oshkosh to write about beer from the perspective of culture and quality instead of treating it as just another commodity. These days, Lundstrom edits The Scene where he continues to cover the Valley beer beat in his Real Beer Man column. Over the years, Jim has been a great help to the beer drinkers of Oshkosh and now he could use a little help from us.

On August 18, while riding his bike, Lundstrom was hit by a 3/4-ton truck with a snow plow attachment. The accident left him with a severely injured left leg and an overwhelming pile of medical bills. Jim is recovering, but he’s badly in need of physical therapy and, without insurance, is in a tough spot. Here’s where we come in. This Sunday, December 12, at O’Marro’s Public House in Oshkosh the Real Beer Man Needs Rehab Benefit will take place from 4-8 p.m. and it’s going to be a great time. There’ll be live music from Bobby Evans, The Madpolecats and that S.O.B. Mike Engle; along with beer specials, food, raffles and more. Best of all, you get to have a real beer with the Real Beer Man. Lundstrom will be on hand wearing the first official SOB t-shirt and he adds, “If any of the original SOBs are still mobile and sharp enough to be in public, be nice to see them show up at our old stomping grounds - the orignal SOBs met in an empty store in the complex where O'Marro's is.”

Shawn is going to open up the bar for the Packer game, so come down to O’Marro’s early and spend the day. Also, I’ll buy a beer from the O’Marro’s tap line-up for the first person who on Sunday can give me the correct answer to the following trivia question: What is the name of the only Ale brewed commercially in Oshkosh between 1935 and 1950. No help, no hints, no cheating. Good luck and we’ll see you Sunday!

|

| Lundstrom - foreground - at the first Society of Oshkosh Brewers Meeting 1991 |

Shawn is going to open up the bar for the Packer game, so come down to O’Marro’s early and spend the day. Also, I’ll buy a beer from the O’Marro’s tap line-up for the first person who on Sunday can give me the correct answer to the following trivia question: What is the name of the only Ale brewed commercially in Oshkosh between 1935 and 1950. No help, no hints, no cheating. Good luck and we’ll see you Sunday!

Monday, December 6, 2010

The Return of Real Beer to Oshkosh

Seventy-Seven years ago this morning, a few people in Oshkosh were waking to the first legal hangover they’d had in 14 years. The full repeal of Prohibition arrived on Tuesday, December 5, 1933 bringing to a close the long mistake that permanently altered the drinking culture of Oshkosh.

The change was unmistakable. The day after repeal, the Daily Northwestern noted that the death of the dry law was celebrated here “in quiet fashion.” There had been an afternoon run on the taverns, but according to the paper most of the celebrants were “old timers” who came of age in the days before prohibition. The Northwestern reported that, “there were only a few locations in which a typical reunion could be held. Many of the famous local bars of yesteryear are gone, snuffed out by the coming prohibition. Some have remained, but they are not quite the same, even though bearing a familiar title. Improvements have been installed, and a new atmosphere created.”

The change was unmistakable. The day after repeal, the Daily Northwestern noted that the death of the dry law was celebrated here “in quiet fashion.” There had been an afternoon run on the taverns, but according to the paper most of the celebrants were “old timers” who came of age in the days before prohibition. The Northwestern reported that, “there were only a few locations in which a typical reunion could be held. Many of the famous local bars of yesteryear are gone, snuffed out by the coming prohibition. Some have remained, but they are not quite the same, even though bearing a familiar title. Improvements have been installed, and a new atmosphere created.”

An especially dour aspect of the “new atmosphere” was the 3.2% beer, which was now the standard. Although the repeal of Prohibition eliminated the 3.2% alcohol limit that had been granted to beer eight months earlier as part of the Cullen-Harrison Act, the Oshkosh breweries made it known that they intended to continue manufacturing and selling the new, smaller beer in the period following repeal. Unless, of course, the public demanded otherwise. And that’s just what happened. The low-alcohol beer that had been so warmly received eight months earlier was just as quickly rejected. Within months, “real beer” was once again the norm.

An especially dour aspect of the “new atmosphere” was the 3.2% beer, which was now the standard. Although the repeal of Prohibition eliminated the 3.2% alcohol limit that had been granted to beer eight months earlier as part of the Cullen-Harrison Act, the Oshkosh breweries made it known that they intended to continue manufacturing and selling the new, smaller beer in the period following repeal. Unless, of course, the public demanded otherwise. And that’s just what happened. The low-alcohol beer that had been so warmly received eight months earlier was just as quickly rejected. Within months, “real beer” was once again the norm.

The Oshkosh Brewing Company took particular advantage of the desire for a stronger lager by selling beer into areas where breweries had yet to recover from the prohibition era. In early 1934, Oshkosh Brewing was shipping beer to Illinois, Minneapolis and as far west as California. Unable to get new labels made in time for shipment they used leftover stock from the pre-prohibition days.

The Oshkosh Brewing Company took particular advantage of the desire for a stronger lager by selling beer into areas where breweries had yet to recover from the prohibition era. In early 1934, Oshkosh Brewing was shipping beer to Illinois, Minneapolis and as far west as California. Unable to get new labels made in time for shipment they used leftover stock from the pre-prohibition days.

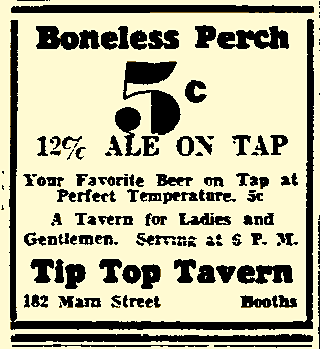

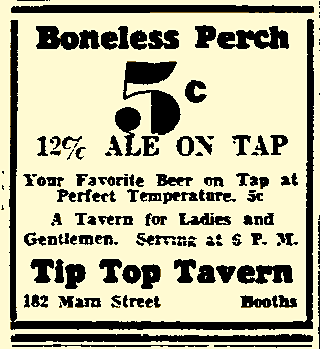

In Oshkosh the backlash against weak beer was immediate. In the months following repeal, higher-alcohol (typically around 5%) beer became something of a fad here. Peoples Brewing released a “High-Test” Holiday Brew for the 1933 Christmas season and throughout 1934 numerous advertisements appeared for taverns selling “High-Powered” beer. The biggest of them all was the 12% ale that the Tip-Top Tavern on Main Street offered on draught for a nickel a glass. Prohibition and the days of Near Beer were truly a thing of the past.

The change was unmistakable. The day after repeal, the Daily Northwestern noted that the death of the dry law was celebrated here “in quiet fashion.” There had been an afternoon run on the taverns, but according to the paper most of the celebrants were “old timers” who came of age in the days before prohibition. The Northwestern reported that, “there were only a few locations in which a typical reunion could be held. Many of the famous local bars of yesteryear are gone, snuffed out by the coming prohibition. Some have remained, but they are not quite the same, even though bearing a familiar title. Improvements have been installed, and a new atmosphere created.”

The change was unmistakable. The day after repeal, the Daily Northwestern noted that the death of the dry law was celebrated here “in quiet fashion.” There had been an afternoon run on the taverns, but according to the paper most of the celebrants were “old timers” who came of age in the days before prohibition. The Northwestern reported that, “there were only a few locations in which a typical reunion could be held. Many of the famous local bars of yesteryear are gone, snuffed out by the coming prohibition. Some have remained, but they are not quite the same, even though bearing a familiar title. Improvements have been installed, and a new atmosphere created.”  An especially dour aspect of the “new atmosphere” was the 3.2% beer, which was now the standard. Although the repeal of Prohibition eliminated the 3.2% alcohol limit that had been granted to beer eight months earlier as part of the Cullen-Harrison Act, the Oshkosh breweries made it known that they intended to continue manufacturing and selling the new, smaller beer in the period following repeal. Unless, of course, the public demanded otherwise. And that’s just what happened. The low-alcohol beer that had been so warmly received eight months earlier was just as quickly rejected. Within months, “real beer” was once again the norm.

An especially dour aspect of the “new atmosphere” was the 3.2% beer, which was now the standard. Although the repeal of Prohibition eliminated the 3.2% alcohol limit that had been granted to beer eight months earlier as part of the Cullen-Harrison Act, the Oshkosh breweries made it known that they intended to continue manufacturing and selling the new, smaller beer in the period following repeal. Unless, of course, the public demanded otherwise. And that’s just what happened. The low-alcohol beer that had been so warmly received eight months earlier was just as quickly rejected. Within months, “real beer” was once again the norm.  The Oshkosh Brewing Company took particular advantage of the desire for a stronger lager by selling beer into areas where breweries had yet to recover from the prohibition era. In early 1934, Oshkosh Brewing was shipping beer to Illinois, Minneapolis and as far west as California. Unable to get new labels made in time for shipment they used leftover stock from the pre-prohibition days.

The Oshkosh Brewing Company took particular advantage of the desire for a stronger lager by selling beer into areas where breweries had yet to recover from the prohibition era. In early 1934, Oshkosh Brewing was shipping beer to Illinois, Minneapolis and as far west as California. Unable to get new labels made in time for shipment they used leftover stock from the pre-prohibition days.In Oshkosh the backlash against weak beer was immediate. In the months following repeal, higher-alcohol (typically around 5%) beer became something of a fad here. Peoples Brewing released a “High-Test” Holiday Brew for the 1933 Christmas season and throughout 1934 numerous advertisements appeared for taverns selling “High-Powered” beer. The biggest of them all was the 12% ale that the Tip-Top Tavern on Main Street offered on draught for a nickel a glass. Prohibition and the days of Near Beer were truly a thing of the past.

Friday, December 3, 2010

Tap Handle Rapture

Every now and then we hit a point where a lot of good tap beer suddenly converges upon Oshkosh and right now were at one of those high tides. The tap menus to your left have all been updated (except for Dublin’s - a little help?) and there’s plenty of quality brew nesting in those lists. Here are a few of the highlights.

Central Waters Hop Harvest Ale is now pouring at O'Marro's and Oblio’s. This is a limited release, wet-hopped, homegrown Wisconsin beer that was covered here when it was first issued in bottles in October. A unique, highly drinkable beer. Also at Oblio’s is Sprecher’s Winter Brew, a chewy dunkel bock that’ll warm you right up.

Becket’s has a batch of winter brews going including Anderson Valley’s Winter Solstice Ale and Shiner’s Holiday Cheer - a dunkelweizen. They also have the great Central Waters Brewhouse Coffee Stout flowing. Looks like a nice way to spend a cold evening.

Fratello’s Fox River Brewing has brought on a couple new beers. I haven’t tried their Vixen Vanilla Cream Ale, but a guy who had it at the table next to mine was raving about it, so that might be worth looking into. Also, they’ve just brought on their German Pilsner, which is going to be the first beer I have tonight after I find my way out of work. I can’t even tell you how I’m looking forward to that.

And last, but nowhere near least, Barley & Hops, fresh off their recent Point Brewery tasting and visit from Brewmaster John Zappa is pouring Point’s 2012 Black Ale. I believe this is the first time this beer has gone on tap in Oshkosh. This is a mild, little devil and a beer that I keep going back to when I’m looking for something a bit lighter, but with good flavor. If you haven’t tried it yet, give it a shot.

Get out and have a great beer this weekend, there’s plenty of ‘em out there!

Central Waters Hop Harvest Ale is now pouring at O'Marro's and Oblio’s. This is a limited release, wet-hopped, homegrown Wisconsin beer that was covered here when it was first issued in bottles in October. A unique, highly drinkable beer. Also at Oblio’s is Sprecher’s Winter Brew, a chewy dunkel bock that’ll warm you right up.

Becket’s has a batch of winter brews going including Anderson Valley’s Winter Solstice Ale and Shiner’s Holiday Cheer - a dunkelweizen. They also have the great Central Waters Brewhouse Coffee Stout flowing. Looks like a nice way to spend a cold evening.

Fratello’s Fox River Brewing has brought on a couple new beers. I haven’t tried their Vixen Vanilla Cream Ale, but a guy who had it at the table next to mine was raving about it, so that might be worth looking into. Also, they’ve just brought on their German Pilsner, which is going to be the first beer I have tonight after I find my way out of work. I can’t even tell you how I’m looking forward to that.

And last, but nowhere near least, Barley & Hops, fresh off their recent Point Brewery tasting and visit from Brewmaster John Zappa is pouring Point’s 2012 Black Ale. I believe this is the first time this beer has gone on tap in Oshkosh. This is a mild, little devil and a beer that I keep going back to when I’m looking for something a bit lighter, but with good flavor. If you haven’t tried it yet, give it a shot.

Get out and have a great beer this weekend, there’s plenty of ‘em out there!

Thursday, December 2, 2010

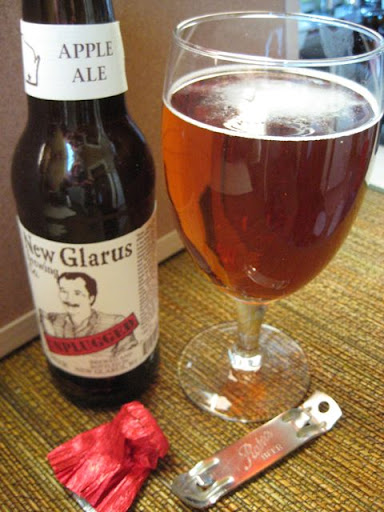

New Glarus Apple Ale

The new Unplugged beer from New Glarus was finally delivered to Oshkosh last week on the back of a serpent promising sex, knowledge and immortality. Of course, that’s bullshit, but Apple Ale is definitely here and if you're up for a fall from grace reenactment this weekend, here’s the beer to do it with.

New Glarus has shuffled Apple Ale through their line-up a few times, now. Its first outing was in a fancy 750 ml bottle packaged like Raspberry Tart and Belgian Red, but that soon passed and the last couple times through it’s appeared as part of the Unplugged series. Regardless of dress, this a simple and beautiful beer.

Made with Wisconsin barley and a mix of apples grown in Gays Mills, the beer pours out like a clean, brown ale with a head that slips away extra quick, leaving you with a cup full of something that could easily be passed off as sparkling apple cider. It’s got that smell, it’s got that look and it’s got that flavor. The aroma is a waft of candied apples with a bump of cinnamon and is a dead-on forecast of the flavor to come. It starts with apple and gains a lactic creaminess as you drink it before finishing off with a nice, tart nip that keeps things from getting too sugary sweet. Hops? Malt? Forget it. Apple Ale is all about apples and that single note simplicity is really what’s most appealing about the beer. It all seems so effortless and straightforward and makes for a very refreshing change of pace from the big, sometimes unrelentingly complex beers that are typical of the seasonal brews this time of year.

A few weeks ago when Stone Brewing announced it was pulling out of Wisconsin, one distributor speculated that the reason Stone couldn’t make headway here was due to Wisconsinites being too “caught-up” in the local beers made by New Glarus, Central Waters, O'so, et al. With beers like this, how can you blame us?

New Glarus has shuffled Apple Ale through their line-up a few times, now. Its first outing was in a fancy 750 ml bottle packaged like Raspberry Tart and Belgian Red, but that soon passed and the last couple times through it’s appeared as part of the Unplugged series. Regardless of dress, this a simple and beautiful beer.

Made with Wisconsin barley and a mix of apples grown in Gays Mills, the beer pours out like a clean, brown ale with a head that slips away extra quick, leaving you with a cup full of something that could easily be passed off as sparkling apple cider. It’s got that smell, it’s got that look and it’s got that flavor. The aroma is a waft of candied apples with a bump of cinnamon and is a dead-on forecast of the flavor to come. It starts with apple and gains a lactic creaminess as you drink it before finishing off with a nice, tart nip that keeps things from getting too sugary sweet. Hops? Malt? Forget it. Apple Ale is all about apples and that single note simplicity is really what’s most appealing about the beer. It all seems so effortless and straightforward and makes for a very refreshing change of pace from the big, sometimes unrelentingly complex beers that are typical of the seasonal brews this time of year.

A few weeks ago when Stone Brewing announced it was pulling out of Wisconsin, one distributor speculated that the reason Stone couldn’t make headway here was due to Wisconsinites being too “caught-up” in the local beers made by New Glarus, Central Waters, O'so, et al. With beers like this, how can you blame us?

Wednesday, December 1, 2010

Spelunking the Beer Caves of Oshkosh

The beer cave is nothing new. Until the early 1900s, when mechanical refrigeration systems became a viable option, local brewers would harvest ice from Lake Winnebago for holding in insulated bunkers to create cold spaces. Here they would store, or lager, their beer for extended periods, usually a month or more, to allow the brew to mature and “ripen” before it went to market. The annual ice harvest was a massive undertaking. In 1910, the year before Oshkosh Brewing built its new brewery equipped with its own ice-making machinery, the company harvested more than 10 thousand tons of ice from Lake Winnebago.

Those days are long gone, but the beer caves remain. A hundred years later, though, the term has undergone an unexpected corruption. In the idiom of gas station operators, the beer cave is now the freezing cold room at the back of the store packed with a volume of straw-hued fluid that would have left our early brewers awestruck. A number of such beer caves have popped up around Oshkosh and most of them are about as interesting as the macro-brewed swill they proffer to keep the punters pie-eyed and jonesing for lottery tickets. But they’re not all of that ilk. We’ve got a couple beer caves in Oshkosh that are a cut above the rest, so let’s take a look at what they have to offer the not-too-discriminating beer snob.

Lets start on the south side of town. A quick trot north from where Glatz, Horn and Schwalm dug their beer caves almost 150 years ago, is the The Condon Party Mart Beer Cave at 1424 S. Main Street. This cave first went into operation two years ago and if you can get past the exorbitant prices tagged to the best of their stock, this is probably the top spot for beer shopping on the south side. The Party Mart treats their beer with a measure of respect by keeping most of it in the cave at a temperature that doesn’t encourage casual browsing. The selection is surprisingly good, too. In addition to the familiar craft favorites by New Glarus, New Belgium and Capital they’ve got a stash of beers you don’t expect to find at a gas station such as Bell’s Two-Hearted Ale and Three Floyd’s Gumballhead. The last time I stopped in I mentioned to the manager that I was surprised by the variety of beer in the cave and without missing a beat he said, “That’s our pride and joy.” If malted beverages comprise the majority of fluid you consume, you’ll probably go broke making the Party Mart your main source of liquid, but in a pinch this place is great.

Now to the north side where the Blue Moose Beer Cave at 708 West Murdock Avenue is like an abridged version of the American beer scene. This place has it all, from the lowest gut-rot malt liquor to the Belgian beers that set the snobs to babbling. Any gas station that regularly has the full line of Chimay on hand is OK by me. And there’s something good about seeing that high-toned ale neighbored with genuine retro-product like Schlitz Tall Boys and Schell’s Deer Brand. The Blue Moose Cave usually has a good stock of New Galrus’ Unplugged beers and always has the coveted Raspberry Tart and Belgian Red on hand. Recently they’ve been bringing in bombers of Goose Island including the Night Stalker Imperial Stout (sold out) and the excellent Sofie Farmhouse Ale. They take the extra step, too, of tacking up little, hand-written signs explaining to the uninitiated what these beers are all about. I’ve asked a couple people at Blue Moose who’s responsible for the good beer coming in and they’ve told me that it’s a group effort, that they have a couple beer lovers on staff. The prices are about what you’d expect from a convenience store (too damned high!), but I’ve seen worse. The only downside, is that the beer cave here tends to be a bit hit and miss. If you see something good you’d better grab it because it might not be coming back.

Now to the north side where the Blue Moose Beer Cave at 708 West Murdock Avenue is like an abridged version of the American beer scene. This place has it all, from the lowest gut-rot malt liquor to the Belgian beers that set the snobs to babbling. Any gas station that regularly has the full line of Chimay on hand is OK by me. And there’s something good about seeing that high-toned ale neighbored with genuine retro-product like Schlitz Tall Boys and Schell’s Deer Brand. The Blue Moose Cave usually has a good stock of New Galrus’ Unplugged beers and always has the coveted Raspberry Tart and Belgian Red on hand. Recently they’ve been bringing in bombers of Goose Island including the Night Stalker Imperial Stout (sold out) and the excellent Sofie Farmhouse Ale. They take the extra step, too, of tacking up little, hand-written signs explaining to the uninitiated what these beers are all about. I’ve asked a couple people at Blue Moose who’s responsible for the good beer coming in and they’ve told me that it’s a group effort, that they have a couple beer lovers on staff. The prices are about what you’d expect from a convenience store (too damned high!), but I’ve seen worse. The only downside, is that the beer cave here tends to be a bit hit and miss. If you see something good you’d better grab it because it might not be coming back.

One bit of shopping advice - in places such as these you really ought to avoid anything that comes in a clear or green bottle. The good beer at these places sometimes hangs around longer than it should, amplifying the strain those sorts of bottles put on the beer. So if you grab some gas and a six of Newcastle Brown Ale there’s a good chance it’s going to be sour enough to make you pucker. I suppose that’s what I get for buying Newcastle.

Want a Beer Cave of your very own? Here you go!

Those days are long gone, but the beer caves remain. A hundred years later, though, the term has undergone an unexpected corruption. In the idiom of gas station operators, the beer cave is now the freezing cold room at the back of the store packed with a volume of straw-hued fluid that would have left our early brewers awestruck. A number of such beer caves have popped up around Oshkosh and most of them are about as interesting as the macro-brewed swill they proffer to keep the punters pie-eyed and jonesing for lottery tickets. But they’re not all of that ilk. We’ve got a couple beer caves in Oshkosh that are a cut above the rest, so let’s take a look at what they have to offer the not-too-discriminating beer snob.

Lets start on the south side of town. A quick trot north from where Glatz, Horn and Schwalm dug their beer caves almost 150 years ago, is the The Condon Party Mart Beer Cave at 1424 S. Main Street. This cave first went into operation two years ago and if you can get past the exorbitant prices tagged to the best of their stock, this is probably the top spot for beer shopping on the south side. The Party Mart treats their beer with a measure of respect by keeping most of it in the cave at a temperature that doesn’t encourage casual browsing. The selection is surprisingly good, too. In addition to the familiar craft favorites by New Glarus, New Belgium and Capital they’ve got a stash of beers you don’t expect to find at a gas station such as Bell’s Two-Hearted Ale and Three Floyd’s Gumballhead. The last time I stopped in I mentioned to the manager that I was surprised by the variety of beer in the cave and without missing a beat he said, “That’s our pride and joy.” If malted beverages comprise the majority of fluid you consume, you’ll probably go broke making the Party Mart your main source of liquid, but in a pinch this place is great.

Now to the north side where the Blue Moose Beer Cave at 708 West Murdock Avenue is like an abridged version of the American beer scene. This place has it all, from the lowest gut-rot malt liquor to the Belgian beers that set the snobs to babbling. Any gas station that regularly has the full line of Chimay on hand is OK by me. And there’s something good about seeing that high-toned ale neighbored with genuine retro-product like Schlitz Tall Boys and Schell’s Deer Brand. The Blue Moose Cave usually has a good stock of New Galrus’ Unplugged beers and always has the coveted Raspberry Tart and Belgian Red on hand. Recently they’ve been bringing in bombers of Goose Island including the Night Stalker Imperial Stout (sold out) and the excellent Sofie Farmhouse Ale. They take the extra step, too, of tacking up little, hand-written signs explaining to the uninitiated what these beers are all about. I’ve asked a couple people at Blue Moose who’s responsible for the good beer coming in and they’ve told me that it’s a group effort, that they have a couple beer lovers on staff. The prices are about what you’d expect from a convenience store (too damned high!), but I’ve seen worse. The only downside, is that the beer cave here tends to be a bit hit and miss. If you see something good you’d better grab it because it might not be coming back.

Now to the north side where the Blue Moose Beer Cave at 708 West Murdock Avenue is like an abridged version of the American beer scene. This place has it all, from the lowest gut-rot malt liquor to the Belgian beers that set the snobs to babbling. Any gas station that regularly has the full line of Chimay on hand is OK by me. And there’s something good about seeing that high-toned ale neighbored with genuine retro-product like Schlitz Tall Boys and Schell’s Deer Brand. The Blue Moose Cave usually has a good stock of New Galrus’ Unplugged beers and always has the coveted Raspberry Tart and Belgian Red on hand. Recently they’ve been bringing in bombers of Goose Island including the Night Stalker Imperial Stout (sold out) and the excellent Sofie Farmhouse Ale. They take the extra step, too, of tacking up little, hand-written signs explaining to the uninitiated what these beers are all about. I’ve asked a couple people at Blue Moose who’s responsible for the good beer coming in and they’ve told me that it’s a group effort, that they have a couple beer lovers on staff. The prices are about what you’d expect from a convenience store (too damned high!), but I’ve seen worse. The only downside, is that the beer cave here tends to be a bit hit and miss. If you see something good you’d better grab it because it might not be coming back.One bit of shopping advice - in places such as these you really ought to avoid anything that comes in a clear or green bottle. The good beer at these places sometimes hangs around longer than it should, amplifying the strain those sorts of bottles put on the beer. So if you grab some gas and a six of Newcastle Brown Ale there’s a good chance it’s going to be sour enough to make you pucker. I suppose that’s what I get for buying Newcastle.

Want a Beer Cave of your very own? Here you go!

Monday, November 29, 2010

Barley & Hess

|

| Zappa |

First, there’s the Beer & Booze Tasting at Barley and Hops this Wednesday night. As usual, $10 gets you through the door and the opportunity to dip into a wide range of beer and spirits. This time the event will be hosted by Point Brewery and their famous Brewmaster, John Zappa. We tend to take Point for granted in these parts, but they’ve been turning out great beer for years, especially under their recent Whole Hog series. Zappa loves talking beer so if you’ve got an interest in the brewing arts here’s your chance to pick the brain of a master. The event runs from 7:00pm - 10:00pm and you can find find out more here.

|

| Hess |

Then on Thursday night, we’ve got something that’ll even suit the teetotalers among us (if there are any). At 6:30pm the Oshkosh Public Library will feature a presentation on the Frank J. Hess & Sons Cooperage of Madison which supplied many of Wisconsin’s breweries with white oak barrels during the first half of the 1900s. Gary and Jim Hess, grandsons of Frank, will be on hand to tell the story of the family business with barrels and cooper’s tools in tow. It’s amazing what these people were able to do with wooden staves and metal hoops. Gary Hess and Jim Hess have been touring the state with this presentation and their story is one any beer-inclined individual will find interesting. Oh, if we could only sample a bit of beer from those white oak barrels. More info here.

Tuesday, November 23, 2010

The Lineage of Oblio's – Part 2

For Part 1 of the Lineage of Oblio’s, go here.

The malaise would linger for several more years, but at the close of 1936 Oshkosh was slowly beginning to emerge from the depths of its slump. That year a Greek immigrant operating a pool hall on Main Street saw opportunity in the vacancy one door to his south. John Konstantine Kuchubas was born in Greece in 1884, the year the Dichmann Block was constructed, and had served in the Grecian Army before coming to America at the age of 18. Eventually settling in Oshkosh, Kuchubas married a local woman named Elsie Zwickey in 1916. Just prior to his marriage, Kuchubas had opened the Pastime Billiard Parlor at 440 N. Main Street, but when the bowling alley next door went under, Kuchubas moved his business to 436 N. Main Street, changed the hall’s name and took his brother-in-law, John Zwickey as a business partner. The Grand Billiard Parlor would become a fixture on Main Street, operating for more than 25 years and though Kuchubas would maintain his stake in the business he wanted something more. The pool hall didn’t hold a liquor license and now that Prohibition had been repealed there was money to be made from the revived saloon culture of Oshkosh. When the appliance shop at 434 N. Main moved out, Kuchubas saw his opening.

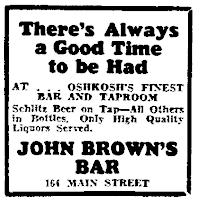

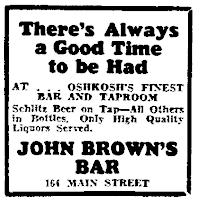

The next time you enter Oblio’s from Main Street look to the wall at your right. There you will find a picture of John Kuchubas sitting behind the bar he had installed for the grand opening of his new saloon on November 27, 1936. To your left will be that same bar, which was built by the Robert Brand & Sons Company at their shop on the corner of Ceape and Court and hauled to Kuchubas’ saloon on a horse drawn wagon. But it wasn’t being called Kuchubas’ saloon, just yet. During the Great Depression America suffered an upsurge of xenophobia and perhaps for this reason the Greek-born Kuchubas decided to leave his name off the marquee. Instead, he tagged his saloon with the most typical of American names, calling it John Brown’s Bar. In fact, Kuchubas and his wife Elsie even went so far as to begin identifying themselves as Mr. and Mrs. John Brown. The innocuous name, though, was no reflection of his new business. From the very beginning, Kuchubas worked to establish a tavern that would stand out among the others along Main Street. He had the interior of the barroom completely re-done and made a point in his early announcements of describing the tavern as a “gentleman's headquarters” where “quality is stressed.” The wording could have been lifted directly from advertisements for the Schlitz Beer Hall 50 years earlier and the similarities didn’t end there. The building was still owned by Schlitz Brewing and Schlitz was, once again, the first beer to go on tap in the new saloon. But it wasn’t just a Schlitz bar, anymore. Kuchubas’ was the first Oshkosh bar in the post-Prohibition era to try and hinge its reputation on the quality and variety of the beer being served. While other taverns of the period were luring customers with sheephead tournaments, cheap liquor and frog legs, Kuchubas distinguished his saloon by pouring the premium beers of the era such as Drury’s Ale and Blatz Old Heidelberg Lager (“Beer of the Year!”).

Kuchubas was obviously proud of his new place and within a year of its opening he was running ads in the Daily Northwestern identifying it as “Oshkosh’s Finest Bar and Taproom”. If anybody in Oshkosh objected to the boast they were uniformly quiet in their disagreement. Though Kuchubas was known as a friendly man, running a respectable saloon, he had a volatile side, demonstrated by an incident that occurred in late 1939. On a Tuesday morning at 1 a.m., after a night working at the bar, Kuchubas returned to his home at 131 Church Ave. where he was jumped by a young man and told to “stick ‘em up.” The 55-year-old Kuchubas did no such thing. Instead, he produced an automatic revolver. As his would-be assailant fled, Kuchubas chased after him, firing two wild shots before abandoning pursuit and calling police. Kuchubas had come by his the hard way. He wasn’t going to let it go easily.

Over the course of the next 16 years, Kuchubas would establish a profitable niche within the center of Oshkosh’s thriving downtown business district. His approach remained consistent over the years; always stressing the quality of the beer and liquor he served and the clean, friendly environment of his room looking out on Main Street. And towards the end of his career his success seemed to have confirmed his sense of belonging to his adopted home. In the last years of the 1940s the tavern was being referred to less often as John Brown’s Bar. Kuchubas had begun using his own name to identify the saloon. Though he would never entirely abandon the original moniker, by the time of his retirement in 1955 the comfortable saloon at 434 N. Main had come to be known by all its patrons as John Kuchubas’ Bar.

After Kuchubas’ departure, little changed at the tavern. The bar was now helmed by an affable Canadian immigrant named John Morrison, who, at 64-years-old, had a lifetime of experience in the tavern business and saw little need to upset the formula established by his predecessor. He changed the tavern’s name to the Morrison Bar, but retained Kuchubas theme of running a “friendly” bar geared towards an increasingly older crowd. Morrison, though, wasn’t around long. Two years after purchasing the business, he passed away and the bar fell to his son, Neal. The younger Morrison would continue on in much the same vein until selling the bar four years later. From 1961 until 1973 the tavern was named The Overflow and was managed by a series of owners, each of whom ran the bar with an almost dogged constancy. The tumult of the era seemed to have little impact on what had become a rather staid tavern.

Over the course of the 1960s Oshkosh had gained a reputation for being a conservative town that showed a different face after dark. Popular night spots such as the Hoo-Hoo Club, the Red Carpet and the Jockey Club were making a direct appeal to a more libertine clientele with strippers, Go-Go dancers and rock bands. There remained, however, a large contingent of less notorious places catering to the traditional Oshkosh bar crowd and The Overflow fell squarely into this division. Throughout the latter part of the 1960s the contrast between Oshkosh bars became glaringly evident in the advertisements that were appearing in the Daily Northwestern. While The Hoo-Hoo Club was filling their space with Rock-House Annie and Katina the Greek Belly Dancer, advertisements for the Overflow featured a caricature of a distinctly middle-aged bartender who, in one quintessential spot from 1968, poses the somber question “So who needs entertainment? When you have a fun-loving group, warm hospitality, pleasant surroundings and good drinks, you don't even miss it!” The cultural divide had arrived in Oshkosh.

The Overflow may have seemed like a hold-out from a bygone era, but its obstinacy was no match for the changes that were afoot. In 1972 Schlitz Brewing, owner of the building at 432-434 N. Main for the past 85 years, sold the property to Charles Lukas, who had been running his Lukas Auto Supply in the south half of the space since 1957. Lukas became just the third owner of the property and within a year the Overflow was gone, to be replaced briefly by a bar named Alfi’s Lounge. In a span of just 14 years, the tavern had run through seven different owners and the upheaval wasn’t over yet.

In 1974 the bar was taken over by Mike Hottinger and Jon Voss who christened their tavern with the name that would stick longer than any that had come before it. Oblio was a round-headed boy living in Pointed Village and was first introduced by Harry Nilsson in his 1971 album The Point! Nilsson said the fable was inspired by an acid trip and the counter-culture reference would not be lost on the new breed of patrons who were increasingly finding their way to Oblio’s. Hottinger and Voss remained just long enough to remodel the game room at the rear of the bar before turning the tavern over to Mark D. Madison, a hard-partying Oshkosher who liked the idea of mixing business with pleasure.

In the summer of 1975 Mark Madison was 24 years old, recently out of college and living near the corner of Evans and Parkway just down the road from the bar where he liked to hang out. It wasn’t just his hangout anymore, though. It may have been hard to tell at times, but Madison was running the place. “I wanted to make my living having fun,” he would later say. For a time, he did. Madison, or “Mooka J” as he was known to his buddies, liked to party and for the next four years Oblio’s would be a funhouse for he and his friends. And Madison had plenty of friends. The bar still had a mix of patrons, but the crowd Madison attracted was younger, many of them college students who came downtown looking for something a little different from the beer bars around campus. Madison gave it to them. The days of Schlitz were over, now there were two Heineken faucets pouring beer into mugs that often didn’t find their way back to the bar. “I had to buy cases and cases of those mugs,” Madison said, “they’d walk right out the door with them.” Oblio’s was now the only spot in town offering beer of a different variety from the indistinguishable light American lagers that had conquered the post-prohibition era. Madison said, “At the time I brought Heineken in there was no good beer at Oblio’s.” Or anywhere else in Oshkosh, for that matter. Madison’s other hot-selling import was Elephant Malt Liquor, a potent Nordic pilsner. “I’ve never seen anybody finish more than a six-pack of it,” Madison said. The wisdom of featuring a beer that quickly renders your customers inert remains to be seen, but it was all in keeping with the spirit of the times and the bar. A bar where Madison sometimes ended the night on the floor. He’d had a good time, but by 1979 Madison knew he needed to move on. “I had to get out of the business,” Madison would say later. “It would have killed me if I hadn’t.”

Oblio’s Lounge was now as well known as any tavern in Oshkosh, but its best days were ahead of it. When two college students took over the bar in 1979 they weren’t exactly sure what they had gotten themselves into, but it wouldn’t take long for them to figure it out and turn Oblio’s Lounge into Oshkosh’s premier saloon.

Mark Schultz and Todd Cummings were no strangers to Oblio’s. “We used to hang out here,” Cummings says. “This was a college haunt for us.” Looking back on it Schultz says, “We turned a drinking hobby into a profession.” When they began, though, they were both rank amateurs. Schultz was 23, Cummings 22 and neither of them had worked in a bar before. But the college roommates living at 1308 Reed Avenue made up for their lack of experience by hiring bartenders from the B & B and the Calhoun Beach Club and it quickly became evident that they were onto something good. “We saw the potential of what this could be,” Cummings said. “We were college students and we had a lot of connections to the University and that gave us a good base to start with.” The first change they made was to install a sound system followed soon after by a change in the beer line-up. “There were four tap lines when we came in,” Schultz says, “Two were Stroh’s and two were Heineken.” Not for long. Cummings was dating a woman who worked for a Manitowoc beer distributor and after she introduced him to Hacker-Pschorr’s Oktoberfest it became a mission for Cummings and Schultz to bring the beer to Oblio’s. “It became my new favorite beer,” Schultz says. “You had to order it in Spring to get it in fall. The first year we ordered 25 barrels and the next we ordered 50 and the year after that 75. Our distributor would have to go through other distributors to get the beer.”

With that, they were off and running. “We could see a certain niche,” Cummings says. “There was a crowd here that liked these beers and that was the beginning of us expanding our beer line-up.” In the 1980s, no other bar in Oshkosh was doing anything like it and Schultz and Cummings had the benefit of an adventurous group of regulars who were interested trying something new. “We had the luxury of trying different beers to see what would sell,” Cummings says. By the late 1980s Cummings and Schultz were looking into installing a micro-brewery in the bar, but shelved the idea due to a lack of availability of good equipment at the time. “We don’t like doing things half-assed,” Schultz said, so they settled on bringing in a rotating selection of American craft beers. “At the time there were a lot of microbrewers making one or two good beers,” Cummings said, “so we thought, what if we bring in the best of these micros instead.” They had hit upon their model for the future. The original four-handle tap box was converted to accomdate 13 beer lines and would later expand to 24 and then again to the current 27 taps. Cummings and Schultz complemented their growing selection with a remodel of the bar wherein they ripped out the drop ceiling to reveal the engraved tin that had been a striking feature of the original Dichmann Block. The legendary tavern at 434 N. Main had returned to and surpassed its former glory.

Schultz and Cummings were now the owners of the building and in 2005 they’d bring the Dichmann Block full circle. When Rudy's Shoe Rebuilders closed in the summer of 2005, Cummings and Schultz opened the wall between the two rooms that had housed the great taverns of Maulick and Kuchubas. It effectively doubled the size of Oblio’s Lounge and in the process created one of the most historically significant public spaces in Oshkosh. Their timing couldn’t have been better. In 2008, Schlitz, the wayward beer that had started it all, made its highly symbolic return from exile to take its place in the Oblio’s tap line. The beer that inaugurated the Dichmann Block 123 years earlier had returned to its Oshkosh home.

That’s a lot of history, but it weighs lightly on Cummings and Schultz who day in, day out usher their bar into the future. As Todd says “It’s happening, it’s just going to get better and better.“

•

Oshkosh street names and numberings have undergone sweeping changes over the years. The street names and numberings in this post reflect the current addresses of the properties and buildings mentioned.

•