|

| Denton Garrison Freeman |

He was born in 1839 on a small farm in Aurelius Township in south-central Michigan. The Freeman family had moved there three years earlier from upstate New York. It was a hardscrabble existence. Freeman's father could neither read nor write. His seven children grew up working the land they carved out of the forest. Denton Freeman got out of there as soon as he could.

Clemansville

Freeman was 17 when he left Michigan heading west. His destination was Clemansville, a small farming community that spanned the border separating the townships of Oshkosh and Vinland in northern Winnebago County.

|

| A marker dedicated in 1946 to the memory of Clemansville still stands near the intersection of County Road T and Brooks Road. |

Freeman arrived in Clemansville in 1857. He made his home on a farm owned by his older sister Hannah and her husband, a recent New York transplant named Spencer Kellogg. Early on, Freeman’s life in Clemansville was much the same as it had been in Michigan. He worked as a laborer on Kellogg’s farm. And he again found himself surrounded by New York settlers who had come to the Northwest in search of open territory.

|

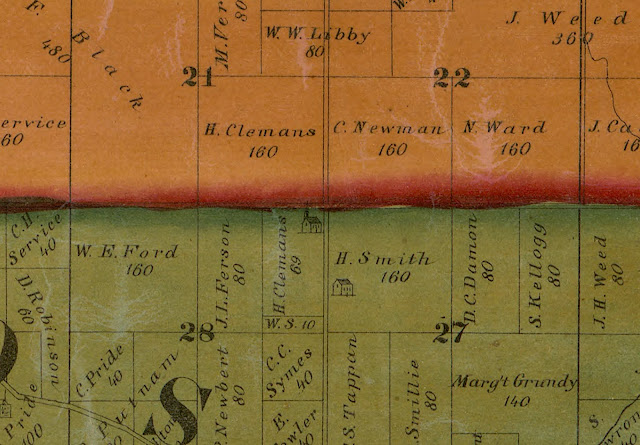

| An 1862 map with Spencer Kellogg's Clemansville farm in Section 27 in the Town of Oshkosh. It was located on the south side of Brooks Road about a mile west of County Road T. |

Freeman remained intent on changing the course that had been set for him. He enrolled at Lawrence University in Appleton and began taking classes at the college’s preparatory school. Between his studies and his farm work, Freeman found time to find a wife. He was 22 in 1861 when he married Mary "Delia" West. Her family had a farm on the other side of Brooks Road in the Town of Vinland. The couple's first child came 11 months after the wedding. She was named Evelyn.

In 1862, Spencer and Hannah Kellogg moved to Brown County, leaving the farm in Freeman's hands. The land wasn’t his, but now he at least had a say over what would be done with it. Freeman appeared to be on his way. But the restlessness persisted.

On December 12, 1864, Delia gave birth to their second child, a boy named George. Freeman left them a month later. He enlisted in the U.S Army and went to Camp Randall in Madison for training. Freeman was going off to fight in the Civil War as part of Company C of the 46th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry.

|

| Union Soldiers training at Camp Randall. |

On March 5, 1865, Company C left Wisconsin and proceeded south. For the next seven months, Freeman helped guard the Nashville & Decatur Railroad line against attacks by Confederate forces. The rail line was a major supply route for the Union Army running between Nashville and Athens, Alabama.

|

| A fortified railroad bridge across the Cumberland River at Nashville during the Civil War. |

On April 9, 1865, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered. The war began winding down. Freeman remained on active duty until September 27. By then he had been made a sergeant. Company C arrived back in Madison on October 2, 1865. Freeman returned to Clemansville and his family. He had a long, cold winter to think about what he would do next.

Hop Fever

When winter ended, Freeman bought the farm from Spencer Kellogg. He paid $500 upfront and borrowed another $2,300 (about $40,000 in today's money), for 80 acres of land in the northeast quarter of Section 27 in the Town of Oshkosh.

|

| A recent satellite view showing the 80 acres (bounded in red) that Freeman purchased from Kellogg in 1866. The blue line marks County Road T. The yellow line marks Brooks Road. |

In the spring of 1866, farms in the Town of Oshkosh and the adjacent Town of Vinland were being transformed. Wheat culture had predominated there since the arrival of the Yankees in the 1840s. But wheat prices had stagnated. Throughout the area, farmers were turning to hops. "Hop Fever" had seized Winnebago County.

For Freeman, the allure of hops proved irresistible. Stories of farmers getting rich on the crop were abundant. Prices were ascendant. A single harvest had the potential to bring in enough revenue to pay off his debt. Freeman went all in.

|

| “A Hop Yard better than a Gold Mine.” Farmers throughout Wisconsin were inundated with ads like this one promising riches from hops. Watertown Republican; February 26, 1868. |

Establishing a hop yard was laborious and expensive. In addition to preparing the soil for a new crop, Freeman purchased rootstock and hundreds of tall oak poles along with wire and twine to build trellises for the vining plants. He needed equipment for harvesting and a kiln for drying. Freeman appears to have spent much of his remaining savings and much of 1866 getting his hop yard in order.

In the spring of 1867, he began planting. By summer, any doubts Freeman may have had were surely being put to rest. Hop prices continued to soar and at the end of the season had reached a record in Wisconsin of well over 50 cents a pound. But Freeman had nothing to sell. The first year of growing was given over to establishing the roots. If all went well his first harvest would come the following year.

|

| High-climbing hops being harvested in a typical Wisconsin hop yard of the 1800s. |

The 1868 season got off to a promising start. By this time, though, Freeman was nearly broke. In early June, he borrowed another $1,600 (about $27,000 in today's money) at 10 percent interest. Freeman had reason to be bullish on his prospects, but he was creating a predicament that could only be rectified by the continuing inflation of hop prices and a banner harvest. Freeman soon faced the stark realization that 1868 was not going to be the year for either.

The first signs of trouble came early that summer. Growers saw their yards infested with a hop-louse that quickly ravaged portions of their crop. More devastating was the drop in prices. The record crop of 1867 led to a surplus that was about to be compounded by a glut of hops from growers new to the market. Prices spiraled down to as little as 10 cents a pound by August.

Freeman knew he was in trouble. On August 18, he sold the eastern half of his property, most of it given over to pasture, to a local farmer named Thomas Rice. The income from the sale wasn't a solution, but it allowed Freeman to stay afloat through the harvest season.

|

| Mature hop cones. Freeman almost certainly grew Cluster Hops, the varietal seen here. |

Freeman brought in his first harvest in early September 1868. The yield was acceptable. The quality was not. He took his hops to market and was offered about 4 cents a pound. Freeman went home with $300 in hand. It was nowhere near enough. Denton Freeman was ruined.

He began preparing for the inevitable. Freeman used the meager $300 and bought an acre of empty land from his neighbor, Henry Smith. Then he returned to the trough, borrowing more money so he could build a house there. The loss of his farm was inevitable. He would need someplace for them to go.

Digging Out

Freeman had another long, Wisconsin winter to stew over what a reckless pursuit it had been. He wasn’t the only victim of hop fever. As one report on the calamity of 1868 noted, "It seems strange that such a large number of intelligent men should be led astray financially, when the facts could be definitely known which pointed to disaster." The clearest path out was bankruptcy. Freeman couldn't accept that.

In the spring of 1869, he began making arrangements with his creditors for dealing with the overwhelming debt he had accumulated. He owed more than $2,000 (about $35,000 in today's money) than he and his farm were worth. Freeman put his remaining 40 acres up for sale. Then he hit the road again.

|

| The southeast corner of County Road T and Brooks Road. After the failure of their farm, the Freeman family moved into a home that was located here on a one-acre lot. |

Freeman's next idea for making money appeared to be every bit as dicey as his gamble on hops. He was going to be a traveling shoe salesman for Niles Stickney & Company of Oshkosh. It was a peculiar career choice for a person who had never earned a living from anything other than the land. He had, however, just stumbled into what would become his life's work.

It was a rambling sort of existence and it seemed to suit him. While Delia and the two kids were bunked at the Clemansville home, Freeman was on the road traveling by rail from town to town in the upper midwest. Armed with a catalog and samples of Stickney-ware Freeman haunted shoe and clothing stores trying to entice new buyers. He was wildly successful. Soon, Freeman was recruited by a larger shoe and boot wholesaler in Milwaukee. All the while he continued to pay down the accumulated debt on his dormant hop yard.

In the spring of 1871, Freeman sold the remaining 40 acres of his Clemensville land. The buyer, Charles Hoffman, also agreed to assume a portion of Freeman’s debt. Freeman was that much closer to being free of the financial failure that dogged him. He was still paying for it six years later when he hatched a scheme designed to take him out of the hole.

Freeman's Gift Concert

Private lotteries were somewhat common and somewhat legal in the 1870s. There was enough gray area around the law that it allowed room for interpretation. Freeman was going to stake a claim in the gray area.

In November of 1877, he announced that he would hold a "Gift Concert" wherein he would sell lottery tickets for a drawing that promised scores of cash prizes and his home in Clemansville as the grand prize.

These games of chance were notoriously corrupt. Freeman, in his promotional material for the Gift Concert, made it clear that his lottery would be free of fraud. He referenced his own "integrity" and "uprightness" promising ticket buyers that "He is a fair and honorable gentleman as all who know him will testify." Perhaps, but Freeman's habit of referring to himself in the third person was less than reassuring.

The prizes were to be awarded on January 10, 1878. A common ploy among these lotteries was to schedule the drawing for a date in the near future and then quietly reschedule it for a later date. The tactic led people to believe their ticket had not been drawn and was therefore useless, leaving a share of the prizes unclaimed. That's exactly what happened with Freeman's lottery.

The final drawing wasn't held until July 2, 1878. A sparse crowd gathered for the event that evening at the Turner Hall on the corner of Jefferson and Merrit. Most went away disappointed. The drawing for the grand prize, the home in Clemansville, was a fiasco. Freeman said he was unable to determine who held the winning ticket. Two weeks later he announced that it had been sold to A.W Straw, a Milwaukee hat maker.

No individual named Straw was ever awarded the grand prize. Freeman retained ownership of the home in Clemansville until he sold it in February of 1879 to a man named David Kronnenberg. Every aspect of the lottery had a crooked look to it. But it appears to have had the desired effect. Freeman was out of Clemansville and out from under the debt that had pinned him there.

The Captain

Denton and Delia Freeman moved to Oshkosh with their two children who were now in their teens. In Oshkosh, Delia gave birth to a girl they named Lulu Belle. The Freeman family lived in a home that once stood on the north side of High Avenue between Division and Jackson streets.

|

| The layout of Freeman’s home from a 1903 map superimposed over a recent view of High Avenue. |

Denton Freeman didn't spend a lot of time around the house. He was often on the road selling shoes. He kept a separate apartment for himself in Milwaukee, which had become his base of operations. In December 1887, Freeman was called back home when both Delia and Lulu Belle contracted diphtheria. Both were dead by the end of the month. He buried them and went back to work.

Freeman remarried in 1903, but still spent most of his time traveling the state selling shoes. He was 72 when he finally ended his commercial travels. After that, Freeman sold shoes from his home.

In 1913, Freeman turned 74 and took a new job as the Quartermaster of the Grand Army Veterans Home at King in Waupaca County. He remained there for the next decade. The folks at the Veterans Home took to calling him The Captain.

|

| Oshkosh Daily Northwestern; October 13, 1911. |

In 1913, Freeman turned 74 and took a new job as the Quartermaster of the Grand Army Veterans Home at King in Waupaca County. He remained there for the next decade. The folks at the Veterans Home took to calling him The Captain.

|

| The Commandant's House at the Veterans Home in King. Built in 1890, the house was designed by Oshkosh architect William Waters. |

As Freeman aged, his identity seemed to coalesce around his nine-month association with the Union Army during the Civil War. After he came back to Oshkosh in 1923, The Captain – as everyone now called him – often spoke about his impressions of the war to local organizations and at functions memorializing Union soldiers. At 90 years of age, Freeman had become the torchbearer in Oshkosh for what remained here of the Grand Army of the Republic.

|

| Denton Freeman appears on the left in the back row. Click the image to enlarge it. Oshkosh Daily Northwestern; June 7, 1930. |

Denton Garrison Freeman died on June 22, 1933 at his home on High Avenue. He was 93 years old. At the time of his death, Freeman was one of just seven surviving Civil War Veterans living in Oshkosh. His grave is in Riverside Cemetery.

No comments:

Post a Comment